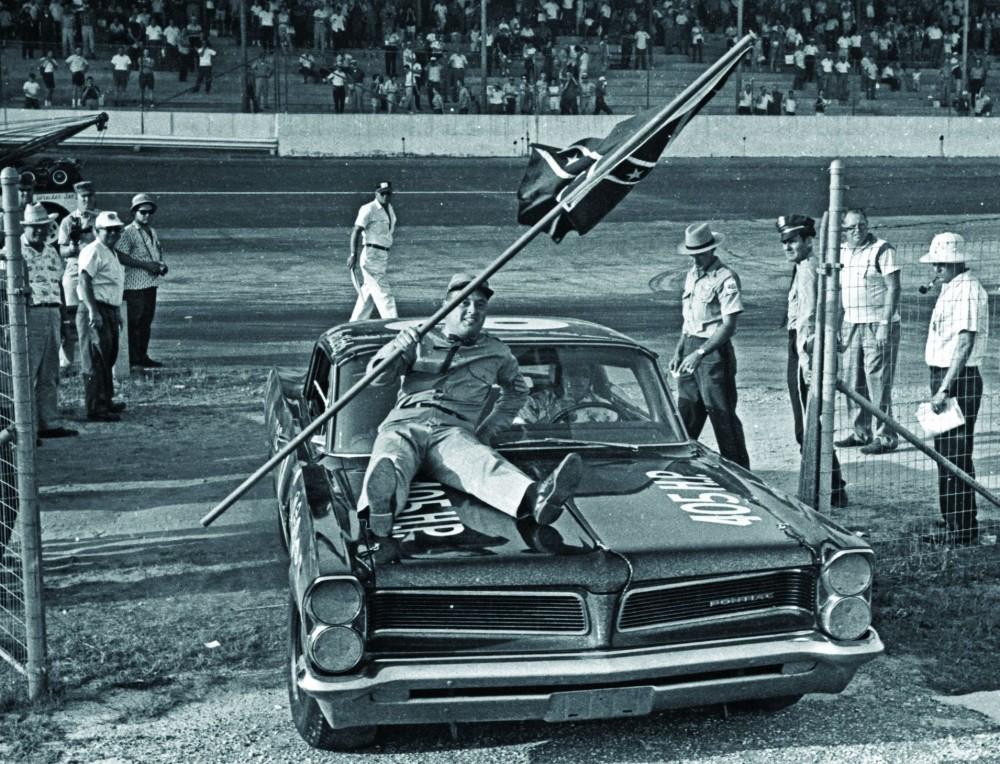

Last year marked the half century since the assassination of John F Kennedy, a milestone in the lives of the baby boomer generation both in the US and abroad. Although never really one for conspiracy theories, even superficial engagement around this story leaves one with doubts around the official accepted version of events, and corresponding doubts about the state of western democracy both before and afterwards. For contemporaries, the overwhelming reaction seems to have been shock, something perhaps comparable with later generations experience around 9/11. It is odd to think that this faded old car was shiny and new, probably someone’s pride and joy on that day in 1963. It did not witness the event, but surely it witnessed conversations, reactions, the atmosphere in a time and place now almost as remote as the lives of the tribesmen of pre-eighteenth century Pontiac, Michigan. It is doubly odd that we can put ourselves into that world, by sitting in this old car and shutting the door.

Last year marked the half century since the assassination of John F Kennedy, a milestone in the lives of the baby boomer generation both in the US and abroad. Although never really one for conspiracy theories, even superficial engagement around this story leaves one with doubts around the official accepted version of events, and corresponding doubts about the state of western democracy both before and afterwards. For contemporaries, the overwhelming reaction seems to have been shock, something perhaps comparable with later generations experience around 9/11. It is odd to think that this faded old car was shiny and new, probably someone’s pride and joy on that day in 1963. It did not witness the event, but surely it witnessed conversations, reactions, the atmosphere in a time and place now almost as remote as the lives of the tribesmen of pre-eighteenth century Pontiac, Michigan. It is doubly odd that we can put ourselves into that world, by sitting in this old car and shutting the door.

Of course, this high flown historical twaddle wasn’t what motivated me to buy it. The muscle era is usually considered to have begun with the 1964 Pontiac Le Mans, specifically with the GTO option package. This put a big motor in a medium sized body, thereby endowing the GTO with adrenaline inducing straightline performance. Now rightly considered a Grade A collectible classic car, these have been out of the reach of pauper writers since the eighties. Absurdly, however, the Grand Prix offers much the same package – medium body size, Pontiac’s venerable 389, in old fashioned high compression and lead additive form – as the GTO, but today it is worth only a small fraction of the prices commanded by GTOs in similar condition. This attracted me, but I would be lying if I said I had sniffed the car out, hunting high and low; rather, it was Monterey week and I was giddy from the auctions, and had just missed a big block ‘66 Impala which was advertised for only $4500 when the Fabricator called up: “I know you love those stack headlight Pontiacs, I think I may have found your car…..”

Styling

The ’63 Grand Prix is usually seen as the first car with Coke bottle waistline. In his book “Chrome Dreams”, a review of US automobile styling, Paul C Wilson says: “This Coke bottle….was also used on the Avanti and the Buick Riviera, but due to the insistence of Pontiac advertising and the ubiquity of the cars themselves it came to be remembered as a Pontiac innovation”. The Coke bottle waist – an upkick in the body behind the door, where the C-pillar joins the body, a mirrored downkick just in front of the rear wheels, and bulging rear fenders is a shape which makes onlookers think of a woman’s hipline, and in that gesture Pontiac developed styling language which has been used ever since to imbue cars with a visceral sex appeal; no longer did Detroit’s steel ape the rockets America was sending into space, now it carried an altogether more earthy subtext.

Fascinating to me is the timing of this change: I am told that car designers used to work in a three year model cycle, three years out. That is to say work started on the ‘63 Grand Prix in 1960, although it was probably conceived in 1959, part of a three year model evolution which started with the ‘62. Usually the first model of the three year cycle is a bridge from earlier designs: the ‘62 Grand Prix had headlights alongside each other, but for ‘63, the headlights were arranged one above another, in a stack, and the Fabricator was right, I do have a particular soft spot for this cue. Although quite unusual now – I have never seen one at a classic car event – the ‘63 Grand Prix sold well, and provided the inspiration for the stack headlights of another Summers sixties favorite, the 65/66 Ford Galaxie / Fairlane. The ‘63 also has concave rear glass ( backlight ), a testament to the era’s experimentation with previously unavailable technologies, while the ‘62 had normal, flat glass. 1959 was literally the height of the fin era, with the Plymouth Fury and Cadillac of that year having the highest tail fins of this short-lived but well-remembered fad. Moreover, this was the age of side mouldings and chrome trim – picture a ‘57 Chevy – the more flash the better, in an effort to look like those moonshot rockets filling the news. Yet the 63 Grand Prix has no chrome, no side mouldings: it is a total direction change away from the cars selling best in the showrooms of 1959 and 60. The final touch is Pontiac’s signature 8 lug wheels, the wheel nuts being arranged around the wheel rim, not clustered on the hub at the center. Allegedly this was some NASCAR trickle down – normal wheels ( at least, the right front ) were known to fall off under the abuse of competition, and the 8 lug was Pontiac’s solution. I can’t help feeling this was perhaps marketing bluster; with the wheel nuts relocated to the rim, Pontiac were able to style a completely new design of wheel, a silver and black ridged chrome capped cone looking thorougly Jetsons and having lost none of their cool in the succeeding five decades.

Overall then, this is a far more subtle, sophisticated styling effort than Americans were used to seeing in their showrooms, a car with the sense of occasion of fifties cars, but without the gaudiness – for Wilson, “It achieved the elusive and self-contradictory ideal of successful luxury car styling, “conspicuous conservatism”.

Performance

The Fabricator has a particular interest in this kind of early sixties Detroit steel, “they were putting these high horsepower motors into these huge land yachts with soft suspension, it was as if they didn’t quite know what they were doing, I mean, they were just tire burning monsters….”

Shortly before buying the Grand Prix, the pair of us had recently experienced a car similar to the Grand Prix in the form of a ‘65 Bonneville the Fabricator had had on loan to sell. This netted out to him using it as a daily driver for a few weeks, and allowing me to take the helm on occasion, bowling along the freeways of Los Angeles, window down, elbow on the door. People tell me the Grand Prix has a trunk “big enough for a body”, but the Bonnie was larger yet, but still elegant, well proportioned. Looking back, it really was the interior which I was most taken with: science fiction kitsch untouched by the Hand of Government legislation. After a late night run down I 5, the Fabricator reported: “It’ll do a buck twenty five but doesn’t want to change direction at that speed”.

My personal experience was direction change or braking required considerable planning and space at anything much above 80 mph; it would however easily attain that speed, clearly had plenty in hand, and with that floaty suspension, it really did feel like “life on the ocean wave”. I was, however, in love: I happen to loathe burgundy, otherwise I probably would have bought that Bonnie.

Through my work at the Blackhawk museum, I know a Pontiac concours judge, and I mentioned to him I owned a Grand Prix. He responded not by asking me about the condition of the car, but with a sparkle in his eye, commented that a Grand Prix was “the first car I did more than 100mph in”.

Buying

The seller of my Grand Prix was a cop in a small East Bay town, and his job, and his frank manner made me feel unusually comfortable indulging in the purchase of a dodgy old car. Ridiculously, I came up from Monterey one evening to kick the tires. I needed to see it run, and we got halfway round the block before dirt in the carb stranded us; by the time the vendor and I had come back with some tools, the Fabricator had the lights working.

By that time it was clear that while grubby, unregistered in a decade and in dire need of tlc items like new fluids, and tires, this was a surprisingly low mileage, genuine car. Small details, such as the fan shroud still being in place made the Fabricator speculate that the mileage, around 62k, was perhaps even genuine. The paint certainly is original, and it still has its California black plates. The VIN indicated it was California built. The hood release is external, and a padlock under the hood speaks to the owner before the cop, who kept it outside in a part of town where people come by, pop the hood and steal whatever parts they can.

A price was agreed, and a few weeks later I came by to pick it up. I had the Boss drive me to the vendors home and follow me over to the storage unit, and this is worth mentioning since it was a one time experience for her helping me with my hobby. She did not help her cause by being somewhat hungover; I did not help her by accepting the vendor’s offer for us to do an oil and air filter change before hitting the road. Thus her patience was well tried by the cops friendly, but garrulous wife, the type who turns the TV on before relentlessly talking over the top of it. When she wasn’t placating a yelling toddler, she suggested “You should get involved in the hobby too” indicating the part restored El Camino on the drive she was helping her husband work on. It was all I could do to keep a straight face as the Boss squirmed; she would commit seppuku before doing any work on a car. The pain was then compounded by the drive across the north bay – quite picturesque for me, but rather less so for her, choking on the blue fumes of lord knows what emerging from the Pontiac, as it rolled under its own power for the first time since Bill Clinton was President. Unable to see the originality, integrity of the car, she fixated on the faded paint and missing backlight: ”Never Again” was the refrain.

Constricted finances have prevented me from tackling the comparatively trivial jobs required to make the car usable. Fitting new tires isn’t as easy as it should be, since most shops cannot balance the wheels, due to the unusual 8 lug design. The backlight was supplied with the car, and that was a stroke of luck, since I am sure finding it would be pretty challenging. Fitting the glass was a specialized two man job taking about two hours – I finally had that done just recently, and when I flinched at the price, the fellow commented that I should be glad I don’t have one of those Chevy pickups with the curved glass “we get at least $600 for them”….

Once it is running, the next step is to consider what to do about the interior. It is as impressive as the Bonnie’s was, but with a console shift and bucket seats; I love the manifold vacuum gauge down by the shift lever. The drivers seat is totally done, collapsed and ass-biting. Dessicated foam leaps from the tops of the rear seats. It needs a headliner, but most of all it needs a clean up, something to deal with the stink of decades of inactivity and dirt accumulation. Rather frighteningly, the steering wheel – a quite beautiful confection of chrome, clear gold plastic and brown plastic – will cost about thirty percent of the purchase price of the car to have refurbished; it is impossible to buy new ones. The problem is less where to start and more where to finish – if I fit a new driver’s seat, headlining, they might look out of place next to the faded glory of the rest of the interior; doing nothing is not really an option, since my goal here is to make this a car women might feel comfortable riding in, rather than reacting with the kind of horror they normally reserve for public squat toilets in Eastern Europe.

After all that, fingers crossed this can be the daily driver I was hoping for when I bought it 😉