There is something special about a flying car, be it the “true” flying car, a work of fifties science fiction, James Bond villains ( Scaramanga’s unforgetable, preposterous yet still wonderful AMC Matador )  or children’s fiction, such as Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

or children’s fiction, such as Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

A conventional car airborn is mighty electrifying too – as a boy I was captured by the Dukes of Hazzard and Rally cars because seeing them leap through the air was so exciting. The onboard feeling when the car goes light over a rise is so much fun because there is an even greater sense of motion than normally, the motion is now in three dimensions instead of two.

Most of us are familiar with the children’s story of Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang. Over the last few years, I have pieced together the following strange connections around the birth of the Flying Car and the Quintessential Englishman, James Bond.

Students of motorsport know there was a real car named Chitty Bang Bang; infact there were three Chittys built, each being, in British parlance “specials”, in US language “hot rods”, one off bespoke custom creations, in this case using surplus World War 1 aircraft engines. They were built by a super wealthy Gatsby-esque figure by the name of Count Louis Zborowski. The son of a Polish émigré on his father’s side and the Astors on his mother’s side, Zborowski inherited his fortune when orphaned at 16; his father had died in 1903, motor racing, while his mother died in 1911. During WW1 he served as a fighter pilot, afterwards turning to motor racing, no doubt in an attempt to replicate the excitement of war.

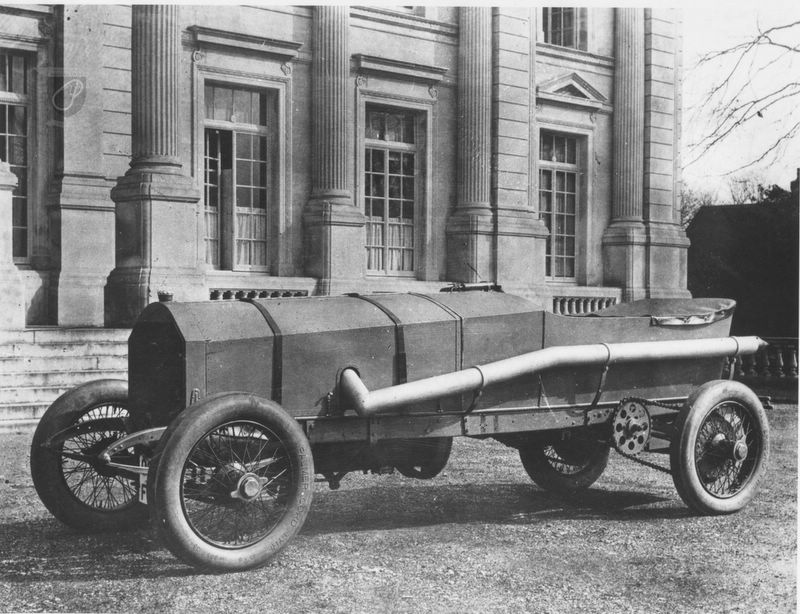

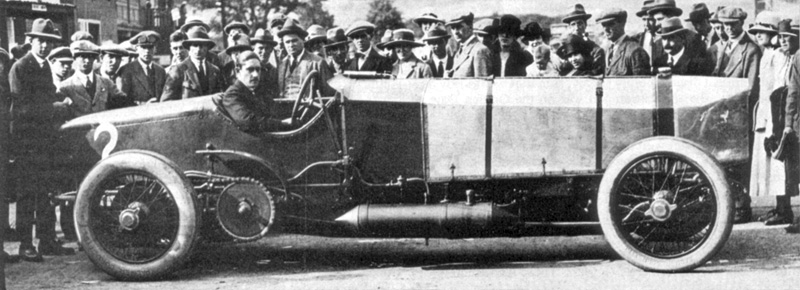

Zborowski built the first Chitty specifically to compete at Brooklands the purpose build banked motor racing track nestling in the Surrey countryside just south-west of London. Since the circuit was egg shaped, without sharp corners, it rewarded sheer horse power; for Chitty 1 Zborowski used a pre-1914 Mercedes 75 hp chassis ( “but lengthened” according to Bill Boddy ( “WB” ) the late editor of Motor Sport magazine and Oracle on everything Brooklands ) installed with a 6 cylinder 24 litre Maybach aero engine, which produced a shade over 300hp at 1500 rpm ( according to WB ) and little if anything in the way of brakes. Chitty 1 won its first race, averaging a hair over 100mph; later the average lap speed would increase to more than 113 mph, with more than 120mph being achieved on the straights. Just stop for a moment and consider what that was like, with primitive suspension and tyres and a track sufficiently rough that cars often became fully airborn. Apparently the chassis flex was so enormous that driveshafts would not work, hence the use of dual chains on each Chitty.

Brooklands was the world’s first purpose built motor racing track, and perforce the world’s first banked track. Infact, the men who built the Indianapolis brickyard visited Brooklands to learn from their experience. Motor racing at Brooklands was very much a high brow social event – the catch phrase of the day was “the right crowd and no crowding” – with well dressed ladies and trackside betting as you might expect at a horse racing meeting. Zborowski was a well known figure at Brooklands not just for his cars, but for the smart uniforms he and his crew of mechanics wore. Some research has indicated that there is a good chance that the title was an assumed one, indeed The Spectator calls it “spurious” ; certainly it could be argued that by competing in the way he did at Brooklands, Zborowski was perhaps looking for acceptance in to British high society, not merely indulging his daredevil passion.

There are various different stories around the origin of the name “Chitty Bang Bang”. The sound itself is not unlike a car trying to start and misfiring. Bill Boddy attributes it to “a lewd wartime song” in his book on Aero Engined Racing cars. However that leaves the juice of the story behind somewhat, lost in British understatement. Zborowski’s squadron had been stationed in France during the war. To leave the airbase required a “chit”, a paper signed by the right person, and these chits were in considerable demand since they were the ticket into the local town, and hence to a pub/brothel, where you could “bang”…..you get the idea.

In practice for a Brooklands meeting in 1922 Chitty 1, with Zborowski aboard, suffered a blowout to the right front tyre, went out of control, first hitting the top of the banking then coming to rest in the infield, having demolished a time keeper’s hut and maimed the occupant. A second time-keeping official saw the car coming and hid in a ditch, seeing “the car passing over his head without doing him any harm” ( to quote Bill Boddy )

Although later repaired and raced, Chitty 1 never fully recovered from the flight, and later was broken up for scrap. ( Ouch !!!! )

Zborowski lived in a lovely country house near Canterbury ,a quintessential English market town, in Kent, south east of London. The house had been bought by his mother just before her death in 1911, and was called Higham, and indeed there was a car built there called the “Higham Special”, later “Babs”, which at one time held the Land Speed Record, before being buried under a beach in Wales. The now disinterred car can be seen at Brooklands.

Again, pause for a moment and imagine being at the wheel of that chain-driven, narrow-tired, 27 litre beast at 170+mph on the wet sand of a beach in North Wales !!!!

All three Chittys were built at Higham. This picture of Chitty 1 just after completion was taken outside the stables, which still exists – indeed I have stood exactly where the photographer was standing:

Zborowski died in 1924, killed, like his father, by the sport, the house passed to the Whigham banking family. Infact the name of the house changed at that time, since Lady Whigham didn’t like the name: Whigham was pronounced with a hard “g”, “Wig Ham”; Higham with a soft “g”, “High Am”; however, local wags ammended that to” Wigam from Higam”, so it can be easily understand why Lady Whigham was keen to change the name.

Lord Whigham was a City of London banker, and employed Ian Fleming’s father; Fleming would go on to create both James Bond and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, the children’s story – notice the extra “Chitty”. Occasionally, business visits included Higham, and the young Ian visited, learning stories of the enormous “flying” racing car. Whether the “flying” in Fleming’s mind was the leaping over the bumps of the banking, or a misinterpretation/exaggeration of the time-keeper’s story of the 23 litre beast passing overhead remains a matter for conjecture.

I visited Higham House in 2006 – at that time it was owned by an lovely, optimistic couple of retired women, who appeared to be doing a cracking job of bringing the house back to a semblance of how it must’ve been in the Gatsby years of the early twenties. Truly, an enormous job, but one they were happy to take a break from to chat with me about Zbrowski, and Fleming. Infact, they confirmed the second part of this story for me. The house is terrific – if you can get to Kent I urge you to go and support them.

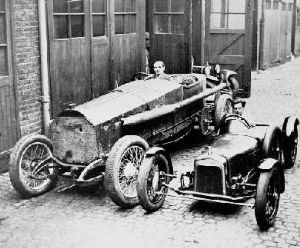

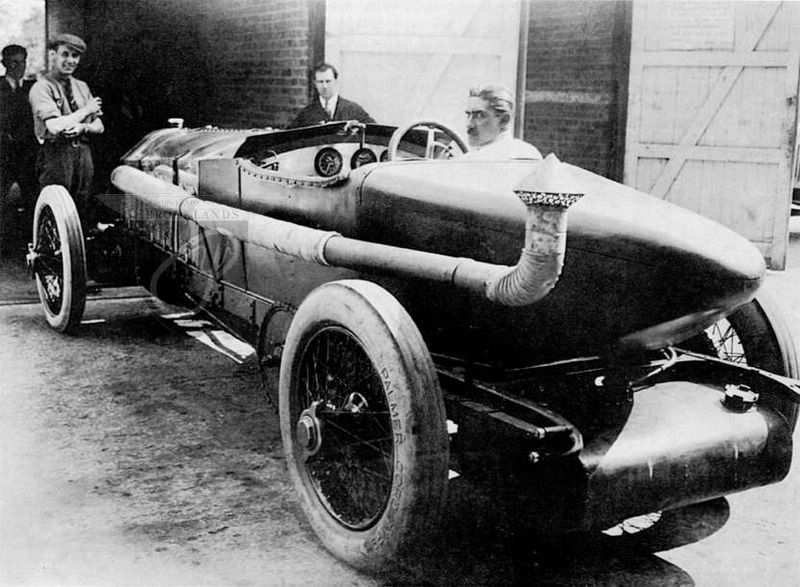

After Zbrowski’s death Chitty 1 was bought by the Conan-Doyle brothers, sons of the creator of Sherlock Holmes. It is thought this picture shows Adrian Conan-Doyle in the car:

Rewind to the London of the 1890s – and here comes the James Bond connection: the runaway success of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories had prompted him to encourage his brother in law, E.W. Hornung to create an equally successful character, one in Holmes’ image but a criminal, not a detective. This was born Raffles, Amateur Cracksman, the gentleman thief, a villain with a Holmesian scientific, reasoned, logical approach to committing crime, not solving it. Raffles is an England-standard cricketer – a strictly amateur game, and one in which a poor scoring innings can be regarded as “better” – more pure, skillful play – than a high scoring one. His day job may be about the most honourable in England, but by definition it did not pay, forcing Raffles to turn to crime to earn a living. However, for Raffles, the endeavour is a sporting undertaking, just like cricket.

George Orwell nails Raffles character when he observes Raffles has “no real moral code, no religion, certainly no social consciousness”, yet “he does have a set of reflexes – the nervous system of a gentleman. Give him a sharp tap on this reflex or that – `sport’, `pal’, `woman’, `King and Country’ – and you get a predictable reaction.” – the reaction of an honourable gentleman.

Raffles caught on, but as a thief was always something of a cad, which limited his long term appeal; it can also be argued that Conan-Doyle was the better writer. However, Raffles made a significant impression on a young Leslie Charteris, who used him as a model to create a hero who might be a thief, but who was honourable, a righter of wrongs in the chivalric, Knights Templar sense of the phrase, indeed a gentleman to a fault – Simon Templar, the Saint. When Fleming visited Higham, and learned of Chitty and Zborowski, one of his favourite writers was Charteris. During the thirties, as the clouds of war gathered, Saint stories changed, developing from being about jewel thefts, to being more about international espionage, usually featuring German stereotypes as villains, while the Saint himself became less Gentleman Thief and far more Gentleman Adventurer.

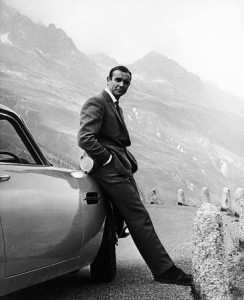

Postwar, Fleming combined his own wartime secret service experiences and womanizing tendencies with the Saint’s sophistication and gentlemanly manner to create James Bond, as suave as the Saint, but hardened by the experience of World War 2, without the Saint’s chivalric asexuality towards women, without honour in his heart.

The connection in the popular mind between Bond and the Saint was completed on the silver screen, with Roger Moore’s an onscreen personification of first one, then the other. In the later, colour Saint episodes, made after the on screen success of the early Sean Connery films, the Saint is often seen to be working in a seemingly freelance capacity for British Intelligence, allied with the US against the Russians or Chinese ( the Chinese villain always seems to be Bert Kwok – almost ironic given that Charteris himself was half Chinese) – like the Saint stories of the thirties, but looking and feeling exactly like the James Bond films Roger Moore would soon star in.

So, does that make Sherlock Holmes James Bond’s grandfather ? Or is my writing style even more digressive than Tristram Shandy ?

Interesting post and thanks for sharing. Some things in here I have not thought about before.Thanks for making such a cool post which is really very well written.will be referring a lot of friends about this.

I just found your site via Ask, good study, heading to sleep now because it’s extremely late but will check you out much more within the morning.

Its difficult to get educated people on this topic, however you sound like you understand what you might be talking about! Many thanks

Nice SEO comments! In the Holmes story, “His Last Bow” which appeared in 1917, the evil German spymaster drives up in a huge 100 hp Benz. Interesting that a few years later, Doyle’s sons end up with a huge stretched Mercedes chassis with a Maybach aero engine bolted to the front. Why they parted it is a tragedy lost to time.