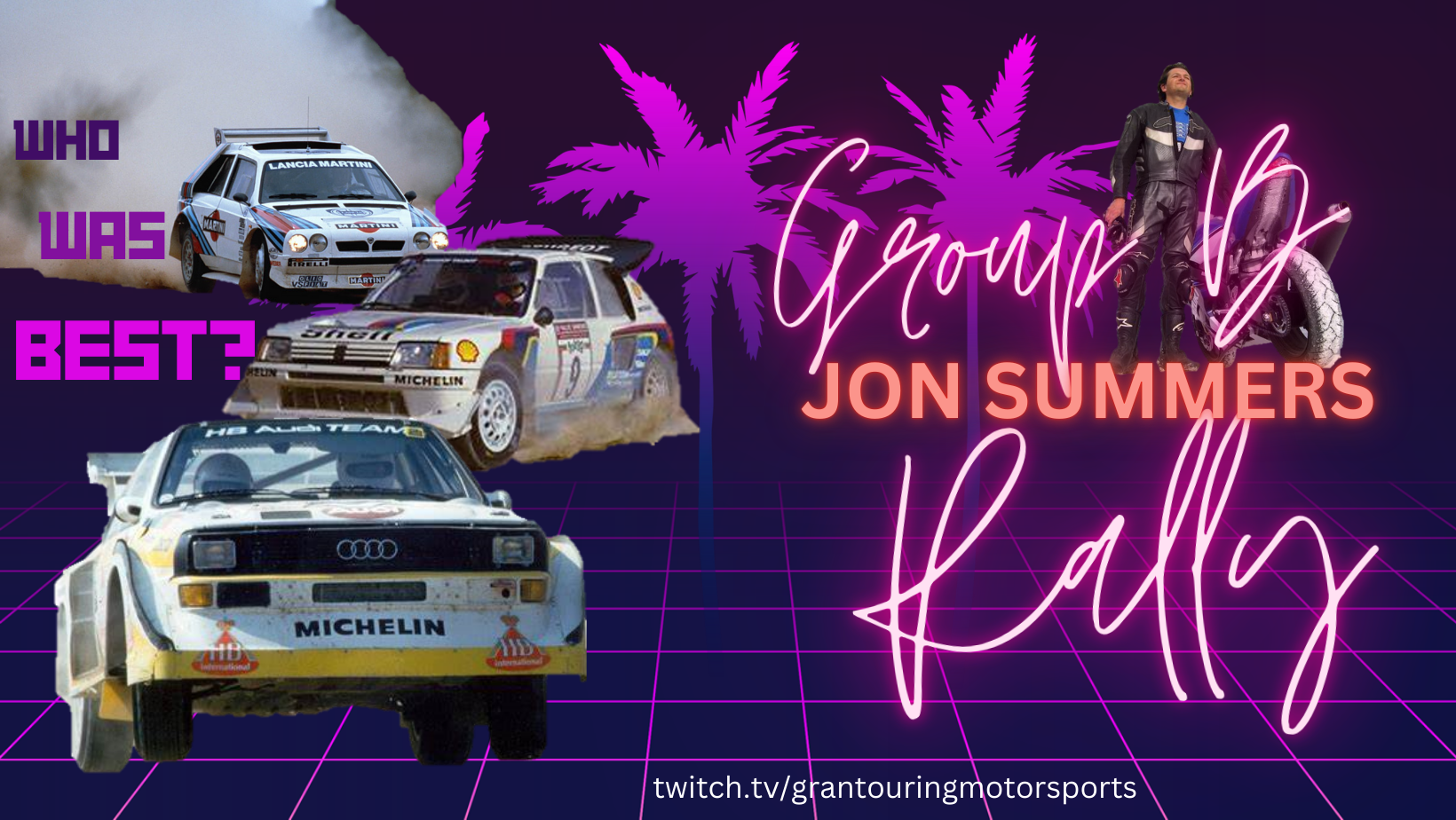

The World Rally Championship is an awesome spectacle which goes to places and touches different fans compared to other kinds of motorsport. For many, the “Group B” years of the eighties represent a high water mark, a golden era.

The cars featured two key innovations: turbocharging and four wheel drive. Power grew from 240hp to 500+ in under five years, and mildly hot-rodded road cars evolved into purpose-built prototypes using the finances, methods, and personnel normally reserved for Formula 1. Yet the rallies themselves were unchanged from when competitors used two-wheel drive cars with under 200hp. They were designed to test driver and navigator endurance, over far greater distances than modern WRC events. The speed and drama captured the imagination of two small suburban boys, Jon in England and Eric in America.

Recently, these cars have re-entered popular consciousness via computer and console games, with high end auctions and car brokers offering examples which have sold for record prices. In discussing this, Jon and Eric discovered they had fundamentally different ideas about which drivers and cars were fastest/best, leading Jon to focus research on this topic.

Part 1 of the presentation will be a synopsis of Group B; part 2 will be a synopsis of the debate. By doing this we shed light on the eternal question, “who was the best driver?” and answer whether “he only won because of the car”.

Notes

Jon Summers is a teaching assistant and guest lecturer at Stanford University. He’s an independent automotive historian, podcaster, and Pebble Beach Docent. Growing up in England, Jon’s first motorsporting love was rallying, which made it onto BBC TV in the seventies. His presentation looks at the wild “Group B” era of the eighties, when turbos and four wheel drive made the cars eye-wateringly fast and also at the drivers heroic enough to compete in them.

Swipe left or right (or use the arrows/dots) to navigate through the presentation slides.

Transcript

[00:00:00] Our next presentation will actually be a zoom presentation. It’s the John Summers one on group B rallying. So the quadro subject I’m sure will come up. Uh, that’s going to begin approximately one o’clock. Uh, our next session will begin at two 15 for those who may be going downtown to have lunch. Uh, have a good lunch.

There’s multiple spots downtown. There’s Curley’s at the foot of the hill. There’s, uh, I’m sorry. There’s the deli at the foot of the hill. Curley’s is to your right. Burger King and Dunkin Donuts are to your left. So we’ll let you figure that out. For those people that are having lunch here, please grab your, your lunch and come back and grab a table so we can enjoy the, uh, John Somers presentation beginning at 1.

And we’ll see you back here for our next presentation at 2. 15. Thanks. Hey, Kip, I want to add to that, to anybody that’s listening, we are actually going to add a special presentation after John goes. It’s going to be a feature film from Peugeot [00:01:00] that includes the Ari Vatnin record run at Pikes Peak. If you’ve never seen it, it’s called Climb Dance.

We’ll be showing that after the Group B presentation.[00:02:00] [00:03:00] [00:04:00]

Hi,

okay. Okay.[00:05:00] [00:06:00] [00:07:00] [00:08:00] [00:09:00] [00:10:00]

All right, let me do my, uh, let me share my screen and begin the, uh, I’m beginning the slide show. Um, can I read my, can you see my slide? Okay. They’re awesome.

All right. Shall I just begin then?

Alrighty. Thank you very much, Bob. Um, and, uh, well, and thank you everybody for taking a, taking us some time out of your lunch break to, uh, to listen to me, uh, to listen to my presentation here on group B rally revisited who was best out. Rawl and Mouton. Or Lancia’s Arlen and Teuvenen, or maybe Peugeot’s Vatanen.

So what we’re going to begin with here is, is some sense of, you [00:11:00] know, how it was received. How did you see these cars? How did you watch this sport of rallying in the 1980s? Um, let’s begin with this little clip of video here.

Now, is everyone else getting sound? Are you getting the sound there? Are we doing sound? Pardon, Eric.

Yeah. How do I connect that box now?

No, no, I can’t. We can’t do this without sound, Eric, can we?[00:12:00]

Um, all right. Are you going to be able to do sound later, Eric? Because I really want to drop off and come back in if I can, then, because the sound, the sound is absolutely critical.

It didn’t give me any of the options to [00:13:00] change the thing.

Okay.

I don’t know where to paste you, Eric.[00:14:00]

I, you know to do, Eric, whilst we’ve got it, I’m going to do my other link in as well, and we’re just going to do that up to the credits. I’m going to do the other link now, a sense of what that’s like as well, and then go. Going forward, I won’t be toggling around with this anymore, I’ll just be going [00:15:00] straight ahead.

Because you know what, it pays to anybody, right?[00:16:00]

And, uh, and up to the time that the bloke starts talking in the second video.

So just just the credits like the cheesy 80s music that was what I how I how I wanted Recently, my limpness issue went away for good, and it was pretty crazy what I did to fix it. I was told by my urologist.[00:17:00]

Well, good morning on this very

Alrighty, so I I’m sorry about that, rather, um So firstly, I’m not the most competent person with this kind of technology generally. And secondly, we did. And try and make it work. And maybe it’s my fault for trying to embed, you know, for trying to actually do the sound, but look, you know, this is motorsports.

So the cars move, so we have to see it moving. Right. And, and also what I really wanted to convey, especially with that Audi clip right at the beginning is the sound it’s that popping and banging of the turbo. And it’s the sheer speed, right? And, and this is what we’re talking about here is it’s this Italian word Uno spettacolo.

It’s a show. It’s a spectacular. It’s kind of this thing, but you’re not going to attract to do it. It comes to you. Now I made these notes right at the beginning of, of this, [00:18:00] of when I was preparing for the presentation. And when I came to write what, what I was going to say, I felt like I was going to struggle to, to improve upon them.

So, so look, I’ve just, I just. Cut and paste in my notes straight into the slideshow. The speed, the violence, the flames. It was impressive in a muddy field, but when you photographed it against the backdrop of the Alps or Kenya, or when it is leaping high above the frozen Finnish tundra, it’s an absolutely unparalleled visual experience.

This is, this is World Rally. Now this is my home throughout the Group B period. It’s 104 straight bit, Flackwell Heath, High Wycombe, England. And I want you to contrast the speed, the violence, the flames, the muddy field, with that vision of dull suburbia. And that’s taken straight from, uh, straight from a street view.

So now let’s talk about the [00:19:00] cars a little bit, and as ever, look, let’s begin with this win on Sunday, sell on Monday kind of, uh, kind of idea. So just how great the Spattacolo was is illustrated by how grip how gripped Eric and I were as young boys. Most Group B cars looked vaguely like the school run specials littering the streets of Europe in the 80s.

Eric’s passion and knowledge is even more remarkable since he lacked that reference point because he grew up in Washington, DC, he had only VHS recordings and his perverse love of Audi, which is a, which was a tough sell in America, given the debacle of the Audi 5, 000, those of you who are old enough might remember that, um, the bottom line is that it.

The bottom line here is that we and thousands like us were gripped by the spectacular, the showmanship of, of Group B Rally. [00:20:00] Yes, Eric. You’re

watching me. You’ve not done the show. Oh, for Christ’s sake. This is the peak, peak. Oh, man. And this is why I should come, right? This is why I shouldn’t, this is why this business of trying to do it on the, at least, and yeah, it’s a good point, Eric, at least if you listen to my podcast, you, uh, you miss the, at least that’s the, the technical ineptitude is largely, uh, is largely trimmed out by that date.

And I even missed the first paragraph of what I was going to say as well. So, so look, let me read that first paragraph. But, uh, And, and, uh, yeah, gosh, this is a triumph of ineptitude. Um, look, it has been said that Group B rally was bigger than Formula One. And while that claim may be doubtful, it’s for certain that there was an enormous buzz in the Group B years, both across Europe and reaching as far afield as Washington, D.

C., [00:21:00] where the young Eric, that’s Eric and the producer guy, um, where he grew up. So, um, I, I talked about how, uh, you know, Eric and I were, were influenced by it because of the showmanship and how in Europe there was this NASCAR win on Sunday sell on Monday. The cars vaguely looked like what you could buy in the showroom that was completely missing in America.

So it’s really remarkable that Eric has the passion that, that he has. And I put this project together very much with, uh, with, with Eric’s help. So, in order to tease out the questions of the greatest car and driver of the period, I had a debate with Eric, which we recorded as a podcast. Our more significant thoughts have been incorporated into this presentation.

The idea was, this was a slick version of the podcast. In, in, in effect, because of my technical stumbles there, it’s been So this is, uh, the, uh, the offices of the head of, of the governing body of motorsport in the Place de Concorde in Paris. That’s right. It’s like [00:22:00] a government office in France. That’s how seriously they take and took governing motorsport.

So Group B was a real, was a rule set, a formula implemented by FISA, the governing body of motorsport from their offices in Paris. Like the Finn era in American automobile design, the time period was short lasting from 1982 to 1986, but its influence outsized before group B rally before group B rally cars had, with a couple of exceptions been warmed over road cars.

Group B added turbos four wheel drive high tech materials and shed weight as rallying gained in popularity. The cars became bespoke prototypes. Instead of 250 horsepower, they had 450 or even more than 500. In short order, the inevitable accidents happened, the rules were changed, [00:23:00] in the name of safety, and Group B was over.

Now looking more closely, we can see that there were in fact two eras of Group B. The first homologation stage required 200 examples of the car to be built and sold to the public, thereby making the car similar to the rally hot rods of the 1970s, such as the Alpine A110, the Lancia Stratos, and of course the Ford Escort RS 1800, as appears on my chest.

In the second phase from 1983, evolution models were allowed. This meant that lower numbers of production versions needed to be built, and in practice, this meant that cars were able to deviate far from their road car routes. 50 horsepower front wheel drive grocery getting hatchbacks became flame spitting mutants with altered wheelbases, oversized and mid mounted engines.[00:24:00]

The relaxation of the homologation rules enabled Formula One in the forests and gave us these true Group B monsters. Now in keeping with the spirit of the age, there’s a conspiracy theory lurking here as well. And that is that the group B rules package, which was developed by FISA with the French and Italian carmakers consulting was all part of some grand strategy to overthrow the decade long hegemony of Anglo American power in motorsport.

So in other words, throughout the 1970s, Ford Cosworth, DFV, Powered cars won all the Formula One races and most of the rallies were won by Ford escorts and the Europeans were upset that the Americans and the British were winning everything in theory. I’m not going to delve into that now.

All right, [00:25:00] so before digging into the past properly, it’s worth examining Group B’s place in the 2020s. Unlike most automotive history, it’s not only appreciated by greybeards, but by young’uns too. And that’s thanks to the power of gaming. In the decades since Group P, gaming technology has steadily improved.

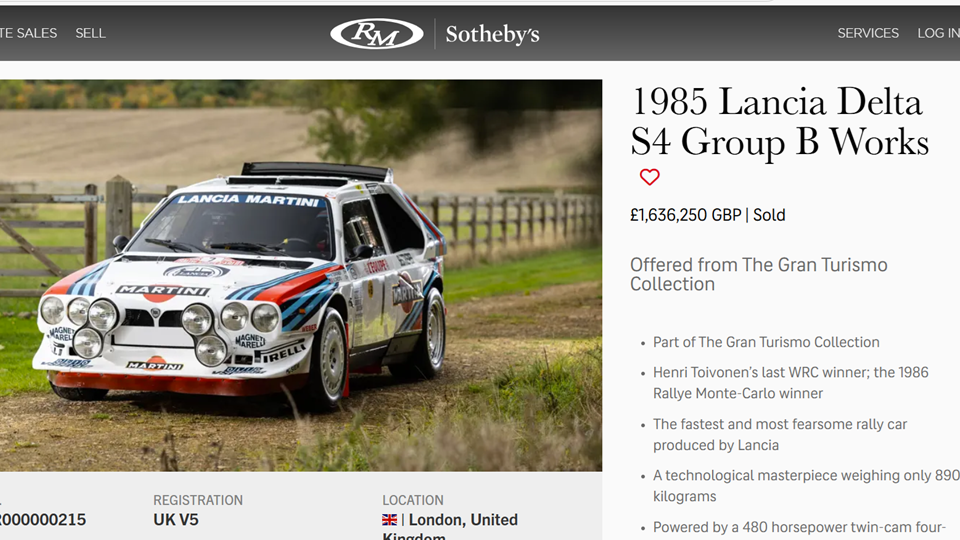

And with it, the virtual recreation of these spectacular cars. Difficult to drive, but fast and awesome to behold, the Spettacolo is as compelling in games as it was on the TV or in magazines of the 1980s. This reverence has translated into the world of investable classic cars, where Group B cars, which have been offered by top auction houses, have brought record prices.

I don’t know if that’s a record price, but it seems to be 1. 6 million dollars for an old rally car is a pretty good price. Now, and, and this is, is how the young’uns [00:26:00] are, are receiving it now. Now, I don’t know, Eric, if we can, this is another little bit of video, this one’s got great music in it. Um, I, I don’t know if you could show this for a minute, Eric, or, or if we should move on and maybe just show this at the end, because really this is similar.

In fact, you know what we’ll do, I’ll come back to this afterwards and we can show it at the end, Eric, before you do Climb Dance. Because this is the But this, this is, this is, this is the 2020s. This is YouTube with modern music that sounds old laid over it and some of the best footage you’re ever going to see of the cars almost running people over.

So I just told you what you were going to see there. It’s still worth you watching it at the end, frankly. Um, and that this way we avoid any more technical challenges that I may have to, uh, that I may try and fail. I used to sell computers. Can you believe that actually made a living selling computer products?

And yeah, I’m that inept with the technology is a remarkable thing. Um, [00:27:00] and you’d be one 20 in Apple yard and his wife, um, the most famous rally car in Britain before the era of, of group B really, um, for the 70 years of motoring up to the recovery of the old. Automobile industry in the post World War II period, the elements characterizing rally in the Group B era had been found in other kinds of motorsport.

That’s to say, sustained fast driving, testing the aptitude and endurance of driver and machine, the critical role of the navigator, and later, the need for a supporting cast of mechanics. Post war in Britain, rallying took the form of navigation and regularity trials. Drive from this town to that, On narrow roads, often with bad signs, often at night in bad weather, you have to arrive exactly at time X.

There are penalties if you’re early, there are penalties if you’re late. There might be a special driving test, kind of like an autocross, you know, reverse [00:28:00] between some cones, that, that kind of thing. And that was called a special stage. These were amateur affairs without prizes or without, and without sponsorship.

The preponderance of Finns and Swedes at the top of world rallying seems to have been down to geographic circumstances. In Sweden years ago, and still in many parts of Finland today, even main roads are not blacktop, they are gravel forest roads. Just as the sweeping quiet roads of Scotland and New Zealand have produced far more than their fair share of Formula One greats, Stuart, Clark and Coulthard from Scotland Frankiti as well, I just thought of, um, Holm, Amon, McLaren from New Zealand.

Basically, if you learn to drive on those fast sweeping roads, you naturally got to be a great driver. If you learn to drive on the [00:29:00] unmade gravel roads of Finland and Sweden, everybody was Bodook. You were wondering why I did that slide, weren’t you? Everybody was Bodook. And if you look at driving, how they learned, how you learned to drive in Finland today, it’s still about car control.

It’s still about learning to slide the car. If you can’t slide the car properly, you can’t pass a driving test in Finland. This is my, this is my understanding of it. A lot of the roads in Sweden now have been paved. So the skills have gone away. But in Finland, apparently still a lot of gravel roads. So remember how in cowboy movies, or in the Dukes of Hazzard, that the heroes always use their local knowledge, like take a shortcut and head them off at the pass?

But it seems that the Scandinavians really had these kind of shortcuts through the forests, using rough tracks, and they perhaps featured obstacles like, you know, a yump over a stream, or maybe you had to drive through the river, or something like that. And it became a sport amongst local [00:30:00] people who knew about these shortcuts, who could do these shortcuts.

As quickly as possible.

This is a map of the 1984 Monte Carlo Rally, and you can see there, it’s, whilst it’s based around Monaco, it expands around the whole region of, of, of the Alps, and you can see where it’s numbered there, where it says SS, each one of those indicates a special stage, and then the cars are expected to drive.

Between these stages themselves, there’s no trucking them between stages. You just get the car, you have to drive the car to the beginning of the stage, then compete on the stage, then drive to the start of the next stage. So in other words, rallying in the group B era with the two traditions, the Scandinavian shortcut through the forest and the British gentlemanly, you know, get from here to there late at night, maybe in some bad weather.

Um, It was these two things combined together. There were penalties imposed for being [00:31:00] late or early to control, so it resembled the event, the British events of the 50s in that respect, but barring an unusual mishap on a road section, the results of the events were determined by who was fastest over the special stages, the bits which resembled the shortcuts.

So, special stages were sections of road that were closed especially for the rally. Cars would set off at one minute intervals in a manner similar to that grandfatherer of motorsport events, the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy. And the winner was the one with the shortest elapsed time. Stages could vary in length from only a few miles to more than 50 miles on some events.

The car needed to be reliable for the road sections, but then be able to take hundreds of miles of gravel stages, 130 miles an hour or more, on unmade forest tracks or gravel. From the early 70s, rallies taking place in different countries around the world had been tied together into the [00:32:00] World Rally Championship, with results giving teams and drivers points, and the totals of those points determining world champions.

It’s important to note that these events were not as homogeneous as other top motorsports series were in the 1980s. As such, it’s worth examining four cornerstone events to understand the scope of the challenges faced by anyone involved, from the driver, navigator and mechanics, to the designers back at the factory.

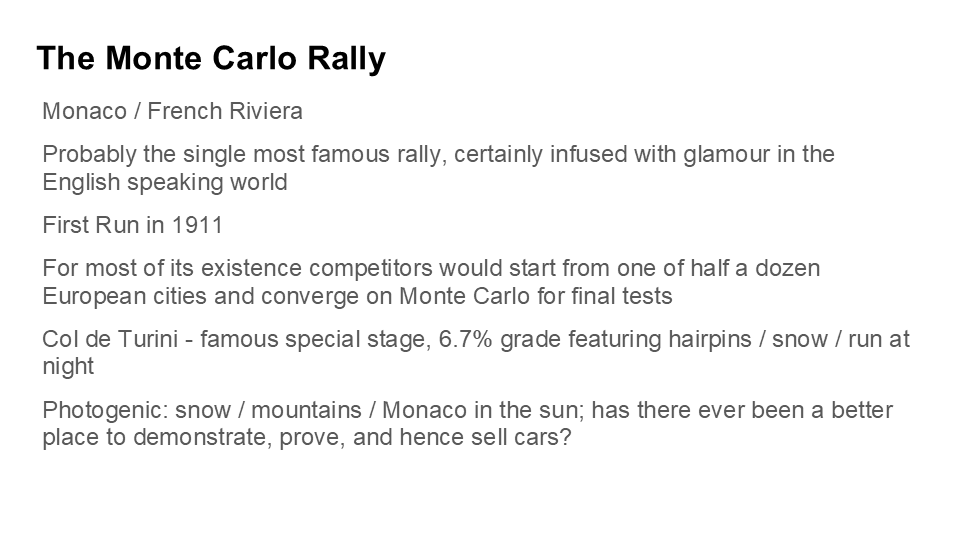

Attrition on these events was very high by design and typically less than half the cars would feel would finish any given event. So the Monte Carlo Rally takes place as we saw around Monaco, largely on the French Riviera. It’s probably the world’s most single, single most famous rally and it certainly infused with a lot of glamour in the English speaking world.

It would be worth introducing to risk. To understand if in, you [00:33:00] know, in Southern Europe, if it had the same glamor, but for, for, for, for Americans and for Brits, especially there’s a real glamor associated with the South of France. The event first took place in 1911, but most of its existence competitors would start from half a dozen different European cities and then converge on Monaco.

So, you know, I’m starting in Stockholm, but you’re starting in Edinburgh and that dude over there, he’s starting in Dublin and the roots were. worked out to be approximately equal. I’ve no idea how it was done. It’s a completely individual and very, very French event in character. Some years they would even race around the course of the Monaco Grand Prix as a final test.

Very bizarre. Um, one of the most famous stages in all rally is the cold that you read. Um, it’s a 6. 7 percent grade. It’s run at night. There’s often snow. Um, um, It’s visually absolutely stunning [00:34:00] and, and look, this, this is really what this is all about. It’s that win on Sunday, sell on Monday thing. It’s super photogenic, cars against the snow, against the mountains.

People have taken cars to Monaco and driven them up hills outside Monaco since the automobile was, was invented. The Nice La Turbie event was taking place in the late 2000s. 19th century, there’s just been no better way to demonstrate, prove and sell cars. And, and hence the specialness of the Monte Carlo rally, the rally of the 1, 000 lakes or the 1, 000 lakes rally, or I think it’s even known as the rally of Finland.

Now, this is the Finnish national event. It was first run in 1951. Um. One of the top guys in the sport, who we’ll talk about later on, a German called Walter Rohr, he wouldn’t even go to the event. And I think that’s really significant because the Finns were so intent on doing the job themselves and [00:35:00] were so competitive with each other that he didn’t just do it.

didn’t feel that he was competitive, didn’t feel like he could show well. Um, so it’s smooth, gravel and very high speed. There’s big yumps or jumps and blind over blind crests. So making the slightest error is an end over end into the woods. And I want to read this quote from Motorsport because it’s just so awesome.

The roads are a network of blind crests, so sharp that the cars inevitably take to the air, losing traction as they do so. But staying on the ground would mean driving too slowly to be competitive. So part of the skill required on the Thousand Lakes is in positioning the car very precisely. Just before the moment of takeoff, in the axes of both pitch and yaw, so that it lands in a manner which will enable the driver to continue unabated, without having to struggle [00:36:00] to keep it in a straight line.

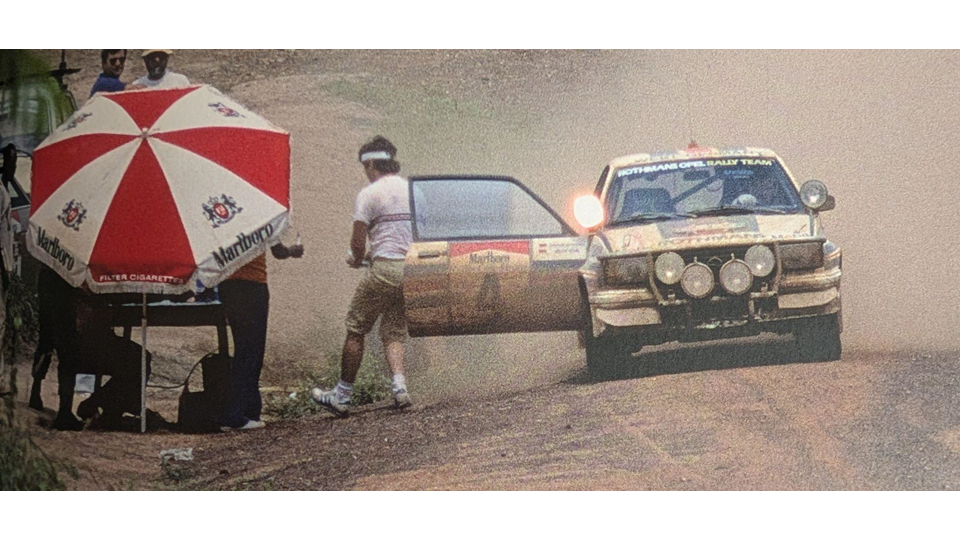

It can be a fearsome event, but do well there, and you can do well anywhere. Um, I wonder if Bo Duke ever thought about the axes of pitch and yaw before he jumped his car. So you thought that one was hardcore, right? What about the Safari Rally? This is Kenya? In 1953, to celebrate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

It really feels like the last century now, doesn’t it? Massive, massive distance, 3, 000 miles. No special stages on this one. Flag them away, see you in Kinshasa. Whoever has the shortest time there is the winner. My god, it’s a real honest to god open road race. It’s the cannonball run, But with zebras and lions and tigers, truly, truly have a look at the pictures.[00:37:00]

I mean, I was going to do pictures, but one doesn’t do it justice. Now you’d have thought that the dude that drove like Boju would win, right? The flat out guy would win, but no, typically the event is won by locals. leaderboard dominated by locals. And this one guy Shektar Mehta was a four time back to back winner between 79 and 83, um, huge variety of terrain, as you’d expect 3000 miles, but, but dominated by powdered sand, rutted tracks and, and characterized by being extremely rough, um, because it rains a lot and often out of season, it would make the roads absolutely impassable.

Um, for, for any kind of car. So quite often, you know, 80 percent of the field would, uh, would, would fail to, to, to finish. And this led to cars that were developed, especially for the event with raised suspension, bull bars, [00:38:00] and snorkels. So you can see the scope of the challenge because they need high suspension and ball bars and snorkels.

So traditionally, the last event of the year and the event which decided the World Rally Championship, certainly in the Group B era, was the RAC Rally in England, in Britain. Um, uh, the acronym RAC is the Royal Automobile Club, and they’re like the American AAA. Um, we have two that are like them. We have the AA, the Automobile Association, and we also have the RAC.

The RAC came later but got a Royal Charter or something, I don’t know the differences between them. But fundamentally, they were the people that organized the event. Um, the route would be around Britain and it would be different every year. So although they would always go to, you know, Northern Scotland and the Kielder forest in Northern England and the, the whale, the, the, [00:39:00] the Welsh valleys and Welsh forests, particularly, um, You know, the less populous areas of Britain, basically the further away from London, the fewer people there are.

That’s a good rule of thumb for England. So nothing around the Southeast, around London, but, but, and, and that we, they would start, you know, the years that, that I remember watching the event, the start towns were, were Bath or Chester or, you know, English market towns, a distance away from, from London.

The first, Time we pivoted away from that business of the, you know, regularity trial simply was in 1960. That was the first time we went into the forests. Um, the event would often take place, it would take place in November. So often the weather would feel pretty Scandinavian. You know, England at that time, the sun is down by four o’clock.

By 4. 30. I was, I remember walking home from school in the dark. So if it’s rainy as well, you can see how [00:40:00] it really suited the Scandinavians far more than, than the Mediterranean, um, Europeans. Um, no pace notes allowed. This is a feature of rallying at the time was that the driver was that the co driver, I’ll talk about this a little bit more later on, but the co driver would tell the driver would have notes and would know where the road went.

So if there’s a blind crest up ahead, he could be like flat over crest because he knew that the road, you know, carried straight on. Whereas if there was a left turn coming up, he would say. Okay. Flat left or you know left heavy braking or left don’t cut because you know don’t cut means there’s a ditch on the inside So you’ll fall off the road if you try and take a race in line around that corner No pace notes on the RAC rally So an unfair advantage for local people and I think that was why we we kept that Why why we Brits kept that in there because it gave You know, British rally drivers a chance against the Scandinavians, but it was super dangerous for Group B.

And we’ll talk about [00:41:00] that in a minute, just because the things were so fast that down the straight. So not knowing what was coming was was really, um, more of an, you know, far more of an issue in a 400 horsepower four wheel drive, uh, you know, Purpose built rally car than it was in a hot rod escort that you and your mate had built in a garage.

So in 1984, they talk about there being 30 hours of continuous motoring with only two short rest periods. In 1985, there was 2, 000 miles to be covered between days three and five of the rally, which included only 10 hours. Hours where the car wasn’t actually rolling. So this is a huge endurance tests. So, so this is right.

It’s public roads, 500 horsepower. The cars haven’t been serviced properly and the drivers are all knackered because they’ve not had enough sleep. So with classic Scandinavian understatement, look, Hanny Mikla, um, [00:42:00] talks about how group B meant that the straights are getting shorter and the corners are coming quicker.

So, despite the, despite the high tech and the big money in the sport, rallying’s culture was not like Formula One or Group C sports car racing. During the 1985 RAC Rally, in a forest stage in the small hours of a rainy night, Markku Alén span his Lancia. The next car along was Juha Kankkunen, a works Toyota driver and future four time world rally champion.

Rather than simply squeezing by, he stopped. Helped and helped Arlen get underway again. This speaks to Raleigh’s history. In remote places where the climate is hostile, motorists stop to help if they see someone struggling, since it’s dangerous to be in that environment without a working vehicle. [00:43:00] This story is far from unique.

A similar anecdote concerns a brief interview with Walter Rall during a Raleigh in 1986. So Walter, Is the Peugeot too fast for the Audi? Roar replies, I only know that Ari, Ari Vatanen, Ari is too fast for me. Rather like the Isle of Man TT, the playing fields were so challenging, the competitors had the utmost respect for each other and absolutely no room for fakery.

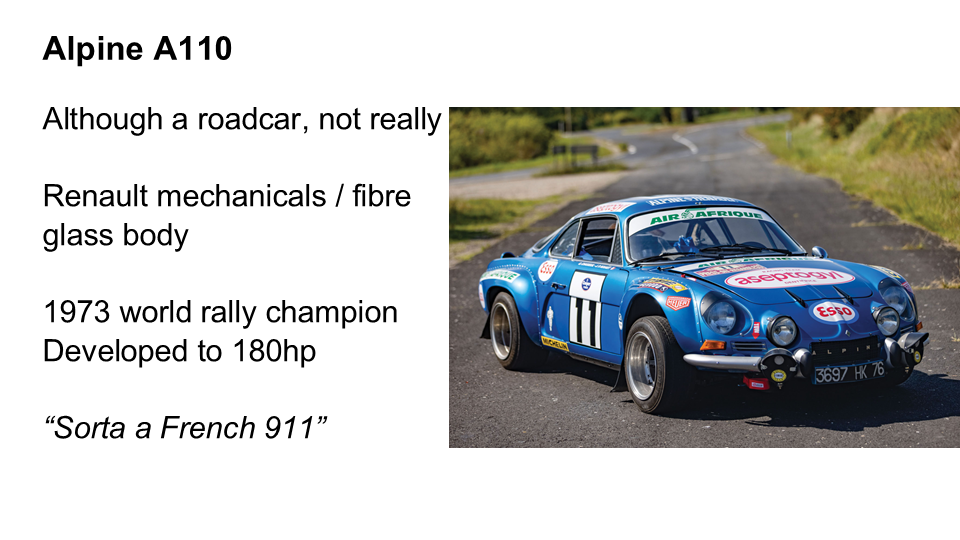

So it’s useful to contextualize the cars of Group B by looking at what had been winning before. So, uh, the first World Rally Championship was won by this guy, the Alpine A110. Um, derived from Fiat, you know, Fiat Mechanicals, but a [00:44:00] fiberglass body. Um, it was either California, um, car guy, hot rod buddy, who Who, when I was, when we were talking about at the one time described it as sort of a French nine 11.

And although I think Alpine people might be offended by that, if you never heard of them before, this is a good way of thinking about them. I put there that they’re developed up to 180 horsepower for most of their life. They didn’t have anywhere near that much. The 1973 world. Rally championship winning car.

It had perhaps 150, something like that. So Renault mechanicals with a fiberglass body. So the Italians, and you’ll see that Lancia were really keen to do this in rally. Generally, the Italians kind of took the piss a little bit and really developed something that can be considered as the first prototype rally car.

The Alpine, it was designed for rally, but it was kind of sold as a road car. And it was kind of, you know, two blokes in a shed in Diet, whereas this was, you [00:45:00] know, people who’d been involved in the Ferrari formula one project being involved in building a rally car. Um, so it’s, uh, the Stratos is, is powered by a Ferrari V6, the, the Dino V6 that was in the, the Dino road car.

And, and, you know, I think if you look closely, the basic architecture of the block is the same, same block that, that Tony Brooks, you know, used to win the 1960 British Grand Prix. That was the last time I think of Formula One. Race was won by a car with an engine in the front. So anyway, Formula One derived engine and that sound right in in the forests of, you know, in the Welsh forest late at night, you could hear the difference between an escort and the last year.

You knew when the last year was coming because it sounded like a V six, not like a howling in line for, um. The joke about these, um, in the trade in the 80s was, uh, [00:46:00] you know, how do you spot a spot a fake Stratos? The panel fit is good. The panel fit on replica Stratos was traditionally better than the originals.

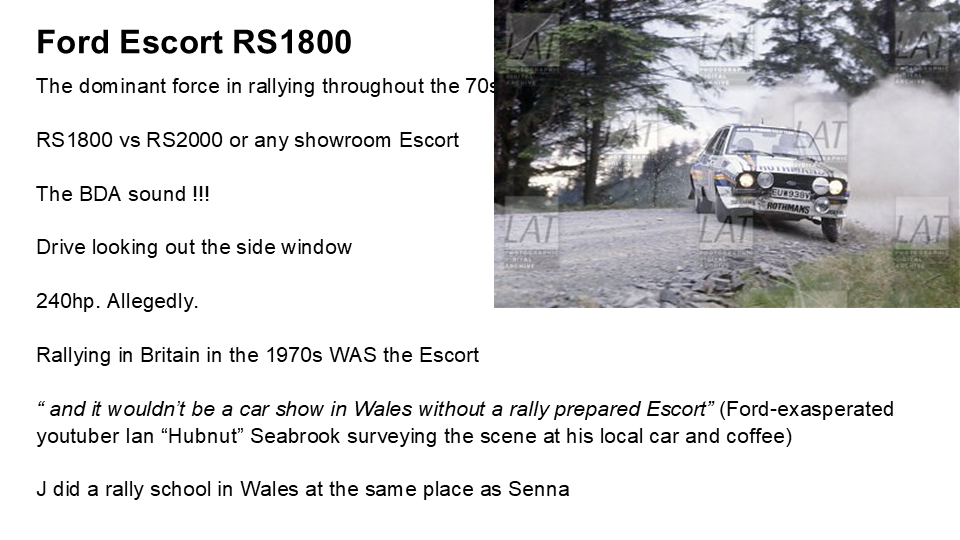

The ones that were homologated and sold absolutely terrible build quality. Um, They were super cool, right? You can see from the picture there, you know, that wedge nose engine in the back, super cool, but never actually won that much. They won some, but not as much as, you know, all of the ingredients might might suggest that eventually when Lancia became probably part of Fiat, Fiat became rather exasperated by the losing of the Lancia and were like, look, we’ll take the Ford Escort, our version of the Ford Escort, which is the Fiat 131 and would have a It’s a hot rod twin cam version of that called the Abarth and then we’ll basically have an Italian escort, which we might be able to beat the escorts with because the Ford Escort is the symbol of rallying in the [00:47:00] 1970s.

I say that as an Englishman, but, but, you know, as I said, as a, as a Brit, because it’s true in Wales and Ireland as well and in Scandinavia. Um, quite what they were using in the Mediterranean countries in this period. I’m not sure. I think if you wanted to win that the escort was, was, was the way to go. Um, I I’ve taught, I’ve mentioned the sound, right?

This is not like an escort you can buy in the showroom. Sure. You could buy a Ford Escort like that in the showroom. They were the best selling car in Britain throughout the 1970s, but, but the best one you could buy from the showroom had about 115 horsepower. It was called the RS 200. Most of them had like 50, That kind of amount, um, the RS 1800 had a 16 valve head on it.

That was what made it different. And that meant that it could rev to nine grand. And it meant that the sound was really the thing which characterized rallying in, in this period. Now, Um, I went and did a rally [00:48:00] driving school, partly ’cause I, I love Ed and Sena and, and Sena went and did this rally school when he was living in England and, and driving for, for Lotus down, down in Wales.

And, and truly I’ve never done another motor sport event where you spent all the time with the cars sideways and you looking out of the side window, you really do look where you’re going. By looking out of the out of the side window, um, you know, and I want to end with with a quote here. I follow a, uh, a British YouTuber by the name of VNC.

Brookie goes by hub now and hub now. I think, and I think I’d feel like this if I lived in England now. Um, there’s an exasperation with the proliferation of Fords. Um, Fords as collector cars are worth far, far more than, than anything similar. We’ll talk about Opel Mantas in a minute. A rally prepared Manta is worth about a tenth of what a rally prepared Escort is worth.

Maybe, maybe not a tenth, maybe, [00:49:00] maybe half, maybe a third. Either way, a rally prepared Escort, today as a collective vehicle is worth a ton more. And, and it’s because of this just British obsession with, with Ford. Um, there’s not like Ford guys and Chevy guys. It’s like, everyone’s a Ford guy. That’s how it feels in, in, in Britain now.

And, and, you know, I have this quote here, it wouldn’t be a car show in Wales without a rally prepared escort. And it truly, it truly wouldn’t.

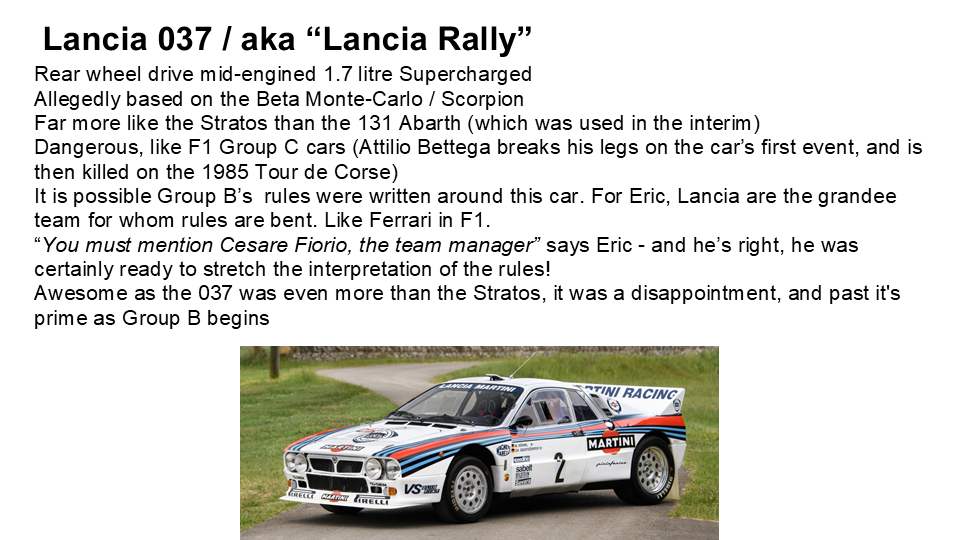

Moving into the Group B era here, this, this, the Lancia 037 here predates Group B, but it’s really comes to, it really walks and talks more like a Group B car. So this is rear wheel drive, but mid engined with a 1. 7 litre motor, which is supercharged. Not turbocharged, supercharged. The Italian word was Volume X, or at least that was the, the model that they launched that, uh, that [00:50:00] caught that it’s based on, on a model that you got in the, in the U.

S. as the Lancia Scorpion, and that we got in Europe as the Monte Carlo, I guess Chevy owned that Monte Carlo name in, in America. That’s why you didn’t get the Monte Carlo name in America here. So in character, far more like the Stratos than the 131 Abarth, you know, the engines in the back. It’s prototype.

It’s, you know, a purpose built rally thing rather than a road car, which being now, which has been converted right from the outset. It was particularly dangerous, not just the speed, but like Formula One cars and Group C cars of the period, there was basically nothing in front of the pedal box. There were the wheels.

There was some tube frame. There was, you know, the brake master cylinder and the steering rack. But that was it. So what that meant was that if you crash the car, you know, it was going to be your legs and ankles that were [00:51:00] taking the impact. And, and, you know, we all know now that, that, you know, running race between 80s Formula One drivers is a standing joke, right?

Because none of them can run because all of them had ankle and ledge injuries, because that was the way that the cars were. We’re designed in this period. Now, I encountered this, this character, Artilio Bottega. I’d heard the guy’s name before, um, he broke his legs on the car’s debut event, and he’s then subsequently killed on on an event in, in a, in an 037.

And whilst, you know, whilst, you know, Those two things don’t necessarily speak to, you know, whilst that may be a coincidence, you do tend to feel, wow, this was, uh, this was a car which was, uh, nowhere near as sturdy as what had gone before. Nowhere near as sturdy as an Abarth, as a 131 Abarth was, for example.

Now, for Eric, Eric feels, and Eric probably knows, has studied the Lazios and the Audis probably more than I have, knows more than I [00:52:00] do, he feels like there’s a good chance Sorry, Eric. Yes. Oh, I was speaking and there was a mumble over the microphone. I thought you wanted to, uh, but, but look, uh, you know, it, it, it, you suggested Eric, the possibility that group B’s rules were actually written around the 7, that the 0 3 7 was built.

And then in the, in the FISA offices, they sort of structured the rules around this awesome new car that was, was gonna finally beat the bloody escorts. Um, You know, is that a hypothesis? Maybe, maybe not. You know, if you follow Formula One, I’m sure you can think of occasions where the rules have been bent to help Ferrari, and one has the sense that perhaps the same thing was going on in Raleigh for Lancia.

Now the next thing Eric mentioned was, you know, you must mention Cesare Fiorio, the team manager. And, and Fiorio deserves a mention because [00:53:00] it’s up to, it’s, it’s on his watch that the super rule bendy cars are designed, and, and it’s on his watch that all these other rule bendy things take place, like. You know, only 100 homologation cars are built.

But when the inspectors come, we inspect 100 in this place. Then we go for a nice long Italian lunch and we quickly move the cars to another place. And, you know, then after lunch, we go and look at the other 100. And here we are, you know, here are the other 100. And yes, Mr. Inspector, we’ve definitely built 200 of them.

Um, so look, The sum up on the 037 is that even more so than the Stratus it was all together an awesome piece of design but it never really achieved the results that were expected of it and as Group B begins it’s past its prime. Now the reason it didn’t achieve its its potential was Audi came to the party didn’t it and when you and when we think about [00:54:00] Group B really we we have to we have to think about Audi.

Um, so this is four wheel drive. It’s got the engine in the normal place, but it’s got a turbo inline five, 2. 1 liters. Now, Audi may have not been involved in any kind of motorsport, you know, prior to doing rally, but the brand has awesome motorsports pedigree. Um, it was founded by August Horch, Horch, Of horse, hawk and an argument to pronounce it.

I, my Italian is bad enough. My German is even worse, but, but look, right. The four rings, um, the Audi have Audi’s four rings of black, uh, Audi’s four rings of silver before the war, the silver arrows, German racing team, auto union, they had four rings as well. They happen to be black. [00:55:00] The four rings symbolized the auto union.

The auto union was, was between DKW Vandera. And Audi, you know, Audi, my understanding at the time was they only made like light cars or something like that, or, you know, I had read one report. They only did ball bearings. I’m not sure if they did that. But the point is that Audi has true motorsports has a true motorsports pedigree.

I mean, Eric, when we talked before, you were like, you know, the thing was prototyped in 1979. It was launched in 1980 or 1980. Either way, the long and short is it took him a bloody long time to make the thing reliable. It was a slow, difficult development of an unreliable technology. Now, the auto union reference is not as left field as it as it might seem, because the basis for the Audi Quattro was a vehicle called the Volkswagen [00:56:00] Iltis, which was a World War Two era jeep affair, a sort of German jeep affair.

That was designed to replace the Kubelwagen or the Volkswagen thing. If you’re like a Volkswagen aficionado, you probably know what those look like. But, you know, I, the, the point is that it had the engine in the front and it had the engine way out front in that, you know, Audi’s and Audi’s going to understeer just like, you know, when it needs the alternator changing, you have to take the whole front clip off and Audi’s going to understeer.

That started here and it started with the Iltis and rather than looking at the Iltis and saying this thing’s an under, under steering and hopeless. No, these two guys, Ferdinand Pieck and Roland Gumper, they set to work making it competitive. And Pierre, that that name is, is well known. He, he went on to be chairman of Volkswagen.

He was the guy who decided since, you know, at the end of the 20th century, since clearly it was going to be [00:57:00] all, you know, green and eco and electric and all of that, we needed a third. I wasn’t horsepower supercar. So he’s the driving force behind the Bugatti Veyron. Um, I personally give him more credit for the Porsche 917 when he was really young.

He was the visionary engineer who led the Porsche 917 project. Um, so yeah, so there’s, you know, excellent engineers involved and guys in the middle of stellar automotive careers involved in building. You know, the Audi Quattro project. Um, so in lots of ways, then, this is Audi proving their staple concepts of four wheel drive, a turbo, and understeer.

It’s them building their brand, and more than that, it’s them paving their way for others, such as Subaru, to build a brand by winning in World Rally. So they did a whole lot more than build their own brand. They showed other brands that they could be done. [00:58:00] Um, long wheelbase versions grow in horsepower from about 270.

So barely any more than the escorts up to about 320 in long wheelbase form. Then a short wheelbase version. Comes and this has 13 inches removed from its wheelbase and this is done specifically to reduce, uh, to reduce understeer. So now the thing will actually, you know, go around corners rather than plow on.

And, and, and now if you look at film, it’s so obvious how bad the understeer was. I, I sort of missed it in period, but looking at film in preparation for, for this, uh, for this document, uh, for, for this presentation today, wow, they were understeerers. Um, later versions of the short wheelbase one, the S1 and the S2 experimented with Kevlar body panels, water cooled brakes, and a dual clutch transmission.

And that was in 1985. That’s right, Audi [00:59:00] had a DCT transmission in 1985. This is how. You know, I for sure that I’ve got to show the contemporary Audi ad here, haven’t I? And this, this tagline Warsprung Dirk Technique. This was, was, um, you know, this, this, this is my mom hates cars. This is a tagline my mom would remember.

That’s how powerful that tagline, uh, that tagline was. And I think, you know, in advertising terms, it’s compelling, right? Because who would have a tagline where most of the people hearing it Can’t even translate what it means. It’s like for most English people don’t speak German. So that tagline is complete gobbledygook, right?

No, it was nailing the technical excellence and peculiarity of Audi. It was awesome. Awesome marketing with, uh, So this is the most competitive of the two wheel drive stuff. This is [01:00:00] front engine, rear wheel drive, 1. 9 litres, normally aspirated. So by in Ascona form, the earlier form with the flatter nose and shorter tail, they developed maybe 240, 250 horsepower.

And then by the time this later, Version came with the man to body rather than the scone of body. Um, that 270 horsepower and, and that’s from Jimmy McCray, who was one of the drivers at the time. That’s why I’m fairly, these horsepower numbers, you, you really got to take it with a pinch of salt, but that number is, is the hard number that I’m quite, I’m quite confident on.

Um, They were super reliable, right? They, they were finishers. Um, and, and in 1982, that finishing and combined with the fact that Audi was still struggling to get the technology right, that meant that Valterra was world rally champion in 1982, the first year of Group B. That’s right. These 500 horsepower, four wheel drive monsters of group [01:01:00] B, the first year of group B was won by, uh, 250 horsepower, two wheel drive.

Um, the Mantas were competitive on British rallies right until the end of the Group B era. And this shows that if you could get ahold of a four wheel drive car, you were doing great if it finished. But if you had a good two wheel drive car, you could still finish well in most regional rallies, you know, non international rallies, right the way up until the end of the Group B era in 1986.

And I put there, look, it’s arguably better than the Lancer 037 and, and, you know, this is that thing of, of, you know, the, the continental types went for really, you know, by that, I mean, the French and the Italians went for really, and the Germans went for really high, high technology. We in Britain tended to stick more with the, you know, the simpler technology, um, which should work well for us in, in, in the past.

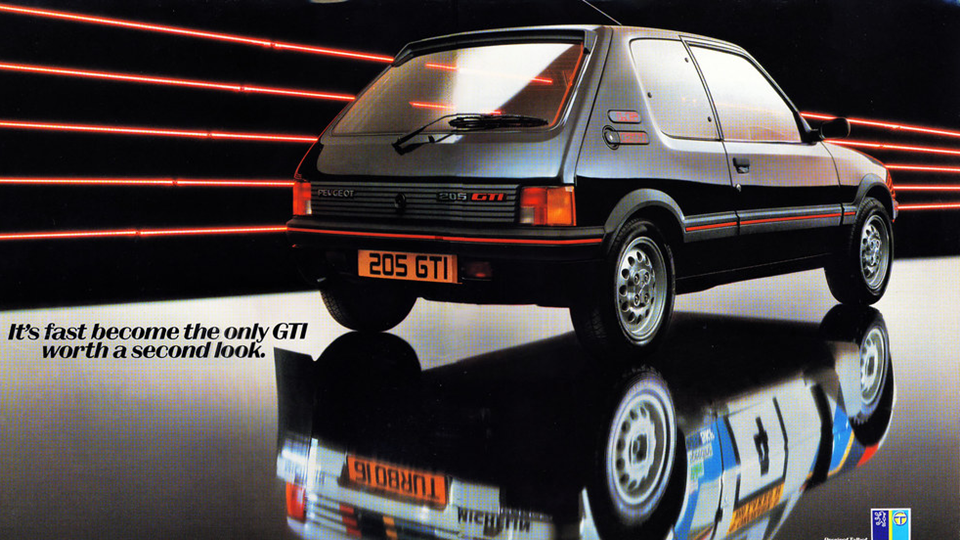

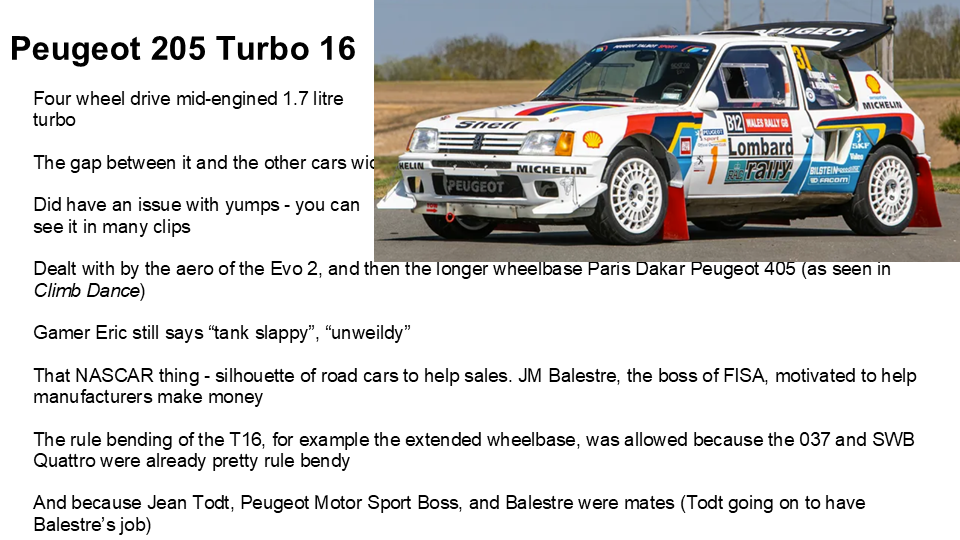

Okay, the Peugeot 205 Turbo 16. [01:02:00] So this is like the Audi in this four wheel drive, but unlike the Audi it deals with that handling problem by putting the engine in the middle like the Lancia 037. No back seat in this Peugeot grocery getter, no a turbocharged 1. 7 litre motor. Now, when it was launched, um, my opinion is, and Eric may disagree with me here, but my opinion here is that it was the gap between it and the other cars was broadest.

It was the biggest step change when the two or five G 16 launched. And really this is the beginning of those evolution rules rather than the homologation rules. Although it came with the homologation rules, Um, you know, and it was homologated. There are 200 of them. It really, it very definitely slipping more into that Evo phase of, of, of the rules, um, in the film, you can see that it really has an issue with jumps that the, it, you know what it needs.

It needs those Hollywood. [01:03:00] Stunt guys that used to jump those Dodge Chargers for the Dukes of Hazard, right? Because what they do is they put three bags of concrete in the trunk of the car. And if you look at some of those Dukes of Hazard jumps when the car lands, you can see the trunk bending, right?

Because you need that weight in the trunk, because otherwise the car’s just going to land on its nose. But with these Peugeots, they do the same thing. They look like they were trying to land on their nose all the time. If you look at them jumping, it’s really not good in comparison to the way that the Audis, uh So this model that you can see in the picture here, this is the Evo 2 that has a slightly longer wheelbase.

It has that giant spoiler on the back and that was enough to really manage the, uh, the, the, the jumping. Um, in a moment, we’re going to watch this awesome video climb dance. Um, that was, that was the T16, but it was badged as the 405 that was Peugeot’s bigger model. It was a sedan. It had, you know, it was a four door sedan rather than a.

Three door hatchback so [01:04:00] you can legitimately make the wheelbase on that longer in order to prove the handling. But as I’ve put in my notes here, you know, Eric tells me from playing on a lot of these rally simulations, the 205 Turbo 16 remains tank slappy and unwieldy. Those were the words you used, Eric, in our pod.

Um, so look, it’s still this thing, right? That the silhouette. Is the silhouette of the shape is going to sell cars. As we saw in that awesome ad period ad, right at the beginning of my presentation. And the boss of FISA, who’s this guy, burlesque was motivated to help the manufacturers make money. In other words, you know, he wanted to help purchase, sell a lot of cars, right?

Cause it was going to save Persia. It did the two Oh five did say Persia. And the T 16 was a big part of the buzz around the two Oh five. It helped that it was a nice car. But, you know, the rallying really, yeah, the [01:05:00] rallying really helped. So you have to say here, so how come if there was, if this was a front wheel drive, 50 horsepower hatchback, how come FISA let a mid engine turbocharged four wheel drive car with a completely different wheel base compete badged as a Peugeot 205, if they were meant to be homologated well, well, I think that.

We’d gotten on a slippery slope, you see, we’d gotten on the slippery slope with the 037 with, that wasn’t really anything like the Lancia Monte Carlo. Um, we’d gotten on a slippery slope with that. And, and then because cutting the wheel base out of the Audi, that was simply going to make it kind of competitive.

And it was still very much looked like an Audi. We let them away with that. So we’d already rules quite a lot. So it was, you know, give them an inch and they’ll take a mile kind of thing. The other reason why I feel like Peugeot were allowed to get away with it was, uh, the boss of [01:06:00] motorsport at the time was a Peugeot motorsport at the time was a chap called Jean Torte, who you might remember goes on to be boss of Ferrari motorsport and then goes on to be the boss of FISA.

So there’s a. Good chance that Todd and the last were friends with each other. And there’s this whole sense of, you know, it’s not what you know, but who, you know, but now it really becomes ridiculous, right? And, and I just want to do some, some images here so you can see how ridiculous it becomes. This is the Lancia Delta that you could buy.

It was launched in the late seventies. It was a Giugiaro design. It’s quite a pretty. It features square squared off styling, right? Not Italian brutalism quite, but it’s squared off, isn’t it? Square headlights, you know, and quite, quite angular styling. And you’ll see it’s a five door hatchback. It was only available as a five door.

There were no three doors. Now this is the press release [01:07:00] of the Group B Lancer Delta S4 rally car. I remember this, it came out just before Christmas of 1984, I think. I remember when it was in the mouse magazines and I looked at it and I just thought it was such a cool car. Now if you look at this area here, And then if I toggle back to my, uh, to my previous slide there, can you see that that, although it looks different, that little area there, if you can see me toggling on the screen there, the rear window there, you could see that that actually looks pretty much the same.

So, yeah, sure. It’s got the flared arches, but, you know, it’s still kind of the same thing, isn’t it? It’s just, uh, it’s just a delta with a body kit. Well, that was what actually turned up at rallies. And I just. I feel like, I mean, just, just look at the shape. Now, sure, this just got the, it’s just got a more aero quad headlight nose on it, hasn’t it?

Yeah, sure, Cesare, that’s all it’s got, right? So how did we get from there to that? This is [01:08:00] what passes as a Lancia Delta by, uh, By the end of the, uh, by the end of the era here.

So the Delta S4 four wheel drive mid engine 1. 7 liter turbo and supercharge. That’s right. We beat that turbo lag by having supercharging at the bottom of the rev range, and then having the turbo cut in what could go wrong. It’s bound to be reliable. This is those special rules for Lancia taken to extremes.

Now, and that, that silhouette commercial that I had at the beginning, you couldn’t do that with the Delta S4. There was no comparison whatsoever. The ante is significantly upped in the, in the horsepower wars. So Eric, you, you mentioned in our presentation, 500, more than [01:09:00] 500 had, um, in that Sotheby’s. That screenshot that I had of the car that was sold at Sotheby’s, they quoted 480, but you know, in this area, it was all about how high you turned up the turbo and there would be a knob and you could just twizzle it and make extra horsepower.

So I feel like all of these numbers, um, they’re just a feature of where you place the knob. The important thing is, is the straights are getting shorter and the corners are coming quicker. That’s the important thing. The straights are getting shorter and the corners are coming quicker. So for Gamer Eric, this, the S4 is smoother than the T16, but still a handful.

So it’s better, it jumps better for sure, but it’s still not easy to drive. And I just want an aside here, you know, part of the reason for the awesome glow around these cars is the way that they look, right? The visual thing, the spectacular, right? That martini livery. [01:10:00] It’s really iconic. I mean, and that is an overused word, but they are the Martini livery.

Um, the white with the, you know, red, blue, purple stripe, that really is, uh, an awesome, uh, look for a car and, and it certainly helps the Lancia’s, uh, um, you know, ups their classicness, if you like, help, help that car to 1. 6 million pounds or dollars or whatever it was. Now look, we Brits, we weren’t going to be left out.

Were we, we, we Austin Rover still existed at that time. So we did our own version of the two Oh five turbo 16 called the Austin Metro six R four. Uh, this was four wheel drive and mid engine like the Peugeot, but unlike the continental offerings, it had a three liter V six normally aspirated engine. So just like.

The Garage Easter [01:11:00] teams of Formula 1 with their 3. 5 litre Ford derived V8 were going to build a bespoke but normally aspirated 3 litre V6. Now these things, these really did sound like Formula 1 in the forest. If the Stratos had got us some of the way there, these things sounded like a Cosworth DFV. And you know, the thought was If the four teams could have, you know, when, and certainly when the car was being developed, the turbos hadn’t yet begun to dominate in formula one, it was getting there.

But when the six or four project started, it still looked like, you know, the garage Easter teams, the Williams’s and so on the Williams and McLaren’s that were in Tyrell’s that was still running the gates. It looked like they could still beat. The, the, you know, ’cause until Ferrari came with the turbo reno, they could never finish a Formula One race, could they?

So there was still that sense that, you know, we can outlast these French and Italians simply by being reliable and, and not breaking down. So, you know what I put in my notes here was [01:12:00] like the Ford Base F1 teams. Why couldn’t we bri, we Brits beat the French Italian turbos with a big capacity, normally aspirated motor, no turbo lag.

More reliable than those. More reliable and. You know, we don’t have those crashy fins driving because boy, they crashed a lot and we’ll talk about that in a moment. Um, so the other thing about this was whilst it might not have had the same straight line as, say, the S4, um, it could corner at a higher speed because it was lighter.

And, and it had that shorter wheelbase and that made it twitchy and harder to handle, but it is a smaller car. Um, and in fact that twitchiness was a problem and in just like the 205 T16, later ones had increasingly longer wheelbases. Now, where Eric, um, Uh, my quote from from Eric here is that I never could get on board with the 6R4.

No turbo. This is never going to work. And that’s a quote from our pod, [01:13:00] Eric. And you expressed our mutual sentiments in period with with that. But something we talked about on the pod was that, you know, had Group B continued The car could have been competitive and it was an alternative way of doing it.

And really it’s a lot more at the Metro 6R4 is a lot more exciting than as a cynical Englishman who was tired of British Leyland and Austin Rover failures. Um, you know, it really could have been something. It was with hindsight, it was a cool alternative. I just want to compare here. Look here, we’ve got a normal Austin Metro.

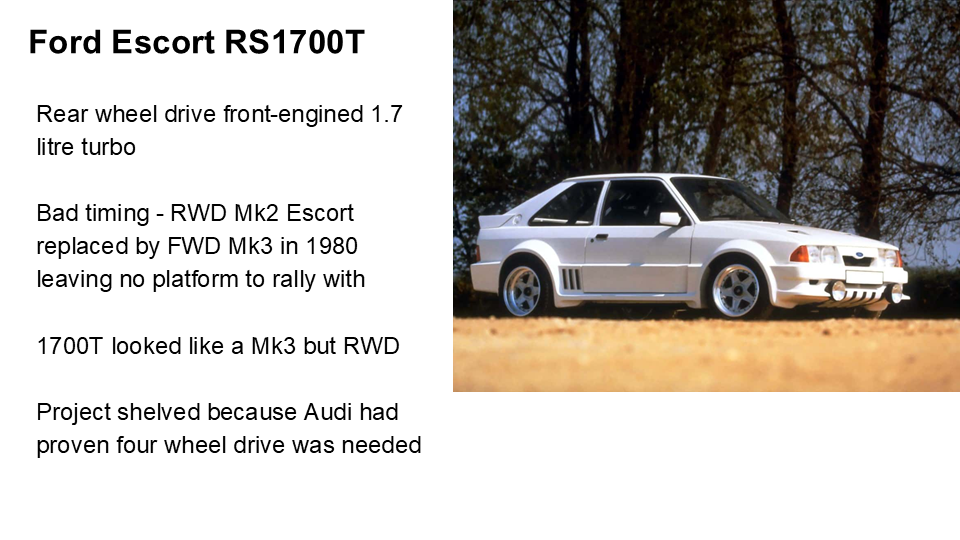

Just look at that normal Austin Metro. Absolute horror show, right? I picked a beige one on purpose, right? Cause that’s what they, and compare it with that awesome. I think they called it an MG Metro, the, the rally one. But, uh, but yeah, Austin Metro, my God. Uh, so what will Ford doing, right? If Ford had won all the time with the Escort, what were [01:14:00] they doing?

Well, it was really crappy timing for Ford. Um, the mark two Escort was rear wheel drive. In 1980, they replaced it with a front wheel drive with the front wheel drive mark three that had a hatchback body style on it, but that left because it was front wheel drive, it left Ford without a platform to rally.

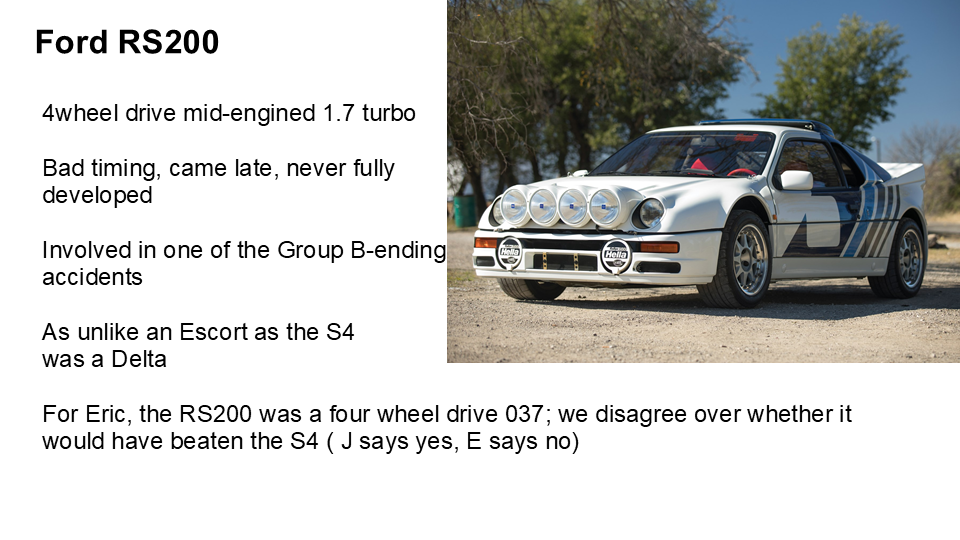

So what they did was they took the front wheel drive platform, developed the turbocharged 1. 7 liter Motor and then rear and then develop the platform to make it rear wheel drive because that was going to work for group B and it’s original, you know, as how it originally looked in 1980, but because Audi had come along with the quattro and were clearly winning everything, it was clear that four wheel drive was needed.

So Ford never really properly campaign. The 1700 T. They just went back to the drawing board to create this, the RS 200. So this is four wheel drive, it’s mid [01:15:00] engined and it’s a 1. 7 liter turbo. So for Eric, this is, is, for me, this was Ford taking on the Delta S4. For Eric, this is more Ford’s version of the 037.

And because we have those different, Perspective, we come at it from a different perspective. We disagree about whether or not if Group B had survived, whether or not the RS200 could have gone on to beat the Delta S4. Um, I think it could have done because I feel like Ford was so strong in motorsport and there was nothing, you know, that Ford were better at than slowly developing a platform.

That was the proof of the escort. So I felt like, you know, even if. The RS200 was just a four wheel drive 037, um, it could go on to beat the S4. Eric says no, Eric says the S4 was more Formula One developed kind of [01:16:00] technology and was just a more, um, developed vehicle, uh, all together. But look, right, it comes too late.

So it’s, it’s launched in early 1986 and by 1986, um, this is when, uh, there are a number of horrific accidents that take place. And in fact, the RS 200 was involved in, in one of the, uh, one of the two key incidents that led to the, to the banning of, uh, of group B. So that’s what Ford were doing, being caught with their pants down, basically.

So now I’m going to talk about the crews a little bit. Um,

I have less than 10 minutes. Okay, let me move quickly here. Um, although we’re talking mostly about the drivers, we should note the importance of co [01:17:00] drivers. Their role on special stages was to read pace notes which they themselves developed. Pace notes detail what happens around the next bend and what the driver should do with the throttle.

Easy, left, opens, flat. On road section between stages, it was often the co-driver at the wheel while the driver caught up on sleep. The co-driver was responsible for navigating the road sections and ensuring punctual arrival at checkpoints while maximizing the time the crew had to service the car. Many pairs lasted throughout the period.

MLA with Arne Hertz moved on with FIA pons and raw with Christian Ger Geer, who we see, uh, who we see here. In the picture, motor racing is always a team sport, but only in motorcycle sidecar racing does a riding passenger play such a crucial role in the team winning. Helicopters were an important and often overlooked element of the Group B spectacle.

They existed to support the teams by ferrying parts faster than the cars [01:18:00] themselves were traveling and to provide spectacular film of the cars at speed during competition. Nowadays, any old YouTuber has some drone panning shots, but in the 80s, the elevated in the landscape moving with the car perspective was not seen outside of movies such as John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix.

In short, the turbos, the turbo shots In short, the helicopter shots turbocharged coverage of Group B. It’s notable that the role they played in contributing to a surprising number of accidents. Because the crowd could not hear the car over the sound of the helicopter, they would be standing in the road when the car arrived.

Now I’m going to talk about the drivers. Talk about the co drivers. Going to talk about the drivers now. How will you be driving, Markku? Now, [01:19:00] maximum attack. This is a huge cliche of rallying. Um, let’s talk about some of the drivers here. I’ve not got a lot of time left, so I want to rattle through these a bit more quickly and then cover my, uh, do my conclusion section here.

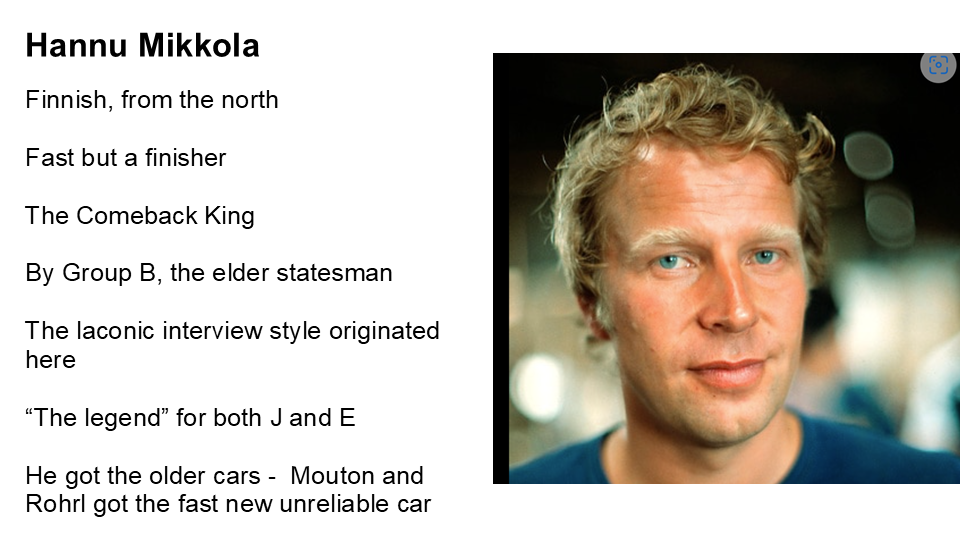

So Mickela. From the North, fast but a finisher, a real comeback guy, you know, he could crash early on, if the car was fine, if the car could be repaired, he would come back and still play as well. Very much the elder statesman of the sport by the Group B era, and the laconic Scandinavian easygoing interview style that we see in Kimi Räikkönen.

Eric and I believe it started with Hannu Mikkola here. He’s the legend for both Eric and I. Um, he was at Audi. Audi would give him the slower car, the older car, and would give his Mouton or Roar the faster and more unreliable cars. Roar is German. He’s a [01:20:00] finisher. He’s fast, but he’s a finisher. He’s champion in 1980 and 1982.

And he beats Audi, the four wheel drive Audi with a two wheel drive car. Afterwards, they asked him to join them. If you look at the film, he’s a noticeably more precise driver than Mikola, and after, he goes on to have an awesome career with Audi racing IMSA, so in other words, he goes from, um, he goes from dirt to pavement racing IMSA in, in North America.

Michel Mouton. Now, the British, I have to quote this, right? The British press always referred to her in period as the pretty French girl. It’s just beyond patronizing, right? But what it speaks to is that it’s tempting to see her as marketing fluff, especially since Volkswagen and Audi’s advertising was so awesome.

But in fact, she was so much more in terms of speed and skill. And as Lynn talked In terms of what she did [01:21:00] around the sport afterwards, um, she was fast, but she was a crasher, um, and got involved in the sport because, uh, I, my understanding is wealthy family from the south of France, Ari Vatanen. He’s from the north.

I have blonde hair like Nicola. Um, fast, but my word, a crasher. Astonishing commitment. Um, the films, if you look at film, the guy could just slide the car longer, more tail out than, than anybody else. Vartanen really looked fast. But like Senna, the frightening commitment was matched with a religious faith.

In other words, it wasn’t that God had his back, but God had given him this talent and my word, he was going to let the talent speak through the way that he drove. So there’s a huge contrast between the way that he drove this wild driving style and then the polite, [01:22:00] calm demeanor. In interviews, and it was that that really captured the imagination of the BBC, the British Broadcasting Corporation, and hence the British public, that you had craziness, and then you had this clipped, perfect English, handsome guy.

It really, it was compelling television. Um, On a personal level, outside of Rally, well inside Rally, during the Group B Erie, he had a horrible accident, end over ended a 205, his seat came off in the car, he got all bashed around inside, although he physically recovered, um, The recovery process left him with depression and it also left him with a fixation that he had AIDS.

And this took place in the 1980s when we didn’t know much about AIDS. And he really wrestled with not being able to rid himself of the idea that he had AIDS as a result of the crash in Argentina. Um, really interesting guy. Went on to be a member of [01:23:00] the European Parliament, believe it or not. My guy, my favorite guy in the period, Markku Arlen, the guy that gave us Maximum Attack.

Um, from Helsinki in the south of Finland, dark hair, not blonde hair, fast, but a bit of a crasher, not as much as Vartanen, but still a crasher. He spent almost his whole career in Italy driving for Lancia and Fiat, and they even call him the Italian Finn because of all the gesticulation. So the British journalists who created Autosport in the mid eighties, Autocourse, the Autocourse books, rated him as number one for 1984 and 1985.

Um, he was born into motorsport. His father was the 1963 Finnish ice racing champion. Um, I loved him in period because of those interviews, because when he was interviewed, um, he, whatever question they asked him, he would always reflect on a mistake that he had made [01:24:00] and be utterly dispassionate in the criticism of his own performance.

Um, our final driver here is Henry Toivonen. He’s Finnish. He’s from Helsinki. His father, Powley, won the very controversial 1966 Monte Carlo rally. Um, so in other words, he, uh, he grew up around rally like, uh, then it was, you know, it was in the, it was in his blood, if you like, um, He was fast, he was a crasher.

Um, he’s the youngest guy here. He’s, uh, the only one under the age of 30. Um, he crashes a Delta S four on the 1986 San Rima rally. He and his co-driver were both killed in a fiery accident. Um, and that’s the end of group B. It’s really his death, which, which ends group B. And I guess my question around this, and I wanna sort of float it up there and then move on due to, due to time here, um.

It’s interesting that [01:25:00] Atelio’s, Atelio Bottega’s death the year before didn’t end Group B. It was just a few years later, just a few months later when there’d been a lot more deaths. That was when we came around to the fact that, you know, maybe these cars are too fast for the, for the situation, for the, for the events as we have them.

Um, so, and for Eric then, Teuvenen is the archetypal rally driver. I’m not sure if he is for me, but for Toivonen, but for Eric, he was. So, um, to come to some conclusions, um, firstly, and this really surprised me when preparing and researching this paper, it seems that local knowledge of a particular event was far more valuable than having the latest and greatest.

Jean Rangnizzi, driving a Renault 5 Turbo, which is a car I’ve not even mentioned in the presentation here, was the class of the field on the 1984 Tour de Corse Rally, where Schecter Mettal won the Safari Rally four [01:26:00] years in a row. This makes choosing the greatest harder than it might be in other kinds of motorsport.

Change was very rapid. This meant that an event like the RAC would see Dave and Steve in an escort built in Steve’s dad’s garden shed, competing with the Works Audi team and their physiotherapists, helicopters, and truckloads of spares. Many careers were limited by serious accidents, for example Vatanen, so in other words he wasn’t rally champion in 1985, in my opinion, because of that accident.

He would have been if he hadn’t had that terrible accident. As new cars were introduced, drivers who’d been uncompetitive in old models became rally winners and championship contenders overnight. In other words, the car is super important. It always is in motorsport, but I’m just reminding you that if you weren’t sat in the right car at the right time, there was no way you were going to win events or win championships.

During the [01:27:00] debate, I said I felt that Group B was completely an accident waiting to happen. And not just because of the huge horsepower, and not just because the horsepower escalated so quickly. Traction and handling improved too, making the cars exponentially faster, even as the sheer drama drew more and more people to spectate, often by standing in dangerous places.

The best Group B rally car depends upon the precise time. By 1983, the Audi had evolved to a point where if it enjoyed a trouble free run, on most events, the two wheel drive runners simply did not stand a chance. Post Quattro, winners needed turbos and four wheel drive. When the T16 was launched, its mid engine gave it a massive advantage, since it could corner much faster than the under steering Audis.

The next generation, the Delta S4 and Metro 6R4, dominated the first event they [01:28:00] entered. Had Group B survived, it’s likely that the S4 and the 6R4, probably with the RS200, would have been the dominant cars. The pace of technological development is demonstrated by Ford and Citroen, each missing much of the Group B era, hobble with low tech, slow cars.

Citroen had a model called the Visa GTI, um, while they feverishly developed more radical offerings, only for the series to be banned before those more radical offerings were ready. So, to conclude, for me, the greatest Group B car. Was the Lancia Delta S4, because I feel that that’s peak Group B. It’s turbocharged, it’s supercharged.

It was the greatest spettacolo. For Eric, the greatest is the 205 T16, because the design was so good out of the can, that once they did [01:29:00] that Evo 2 package, that was the only tweak they needed to make. They still had something that was a rally winner. Now, a third perspective might be that you could argue that greatness, if this was all about win on Sunday, sell on Monday, where are these brands now?

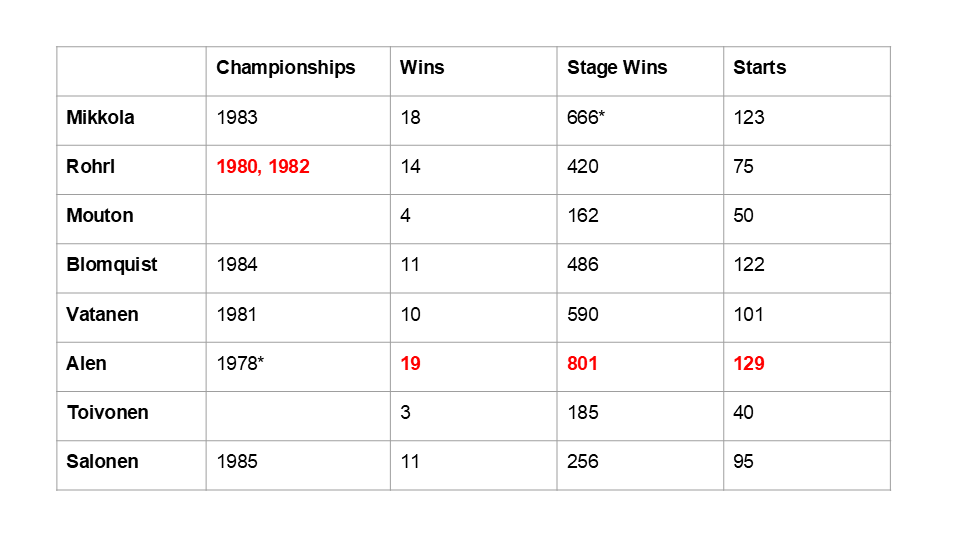

Well, Lancia is dead. Peugeot is a struggling member of, of Stellantis and Audi. Well, they are going from strength to strength, aren’t they? So perhaps based upon that measure, Audi were the most successful. I always do my stats slide, don’t I? And, and, uh, I’m going to because if because I’m conscious that I’m pushed for time, I’m going to let you have a little glance at that.

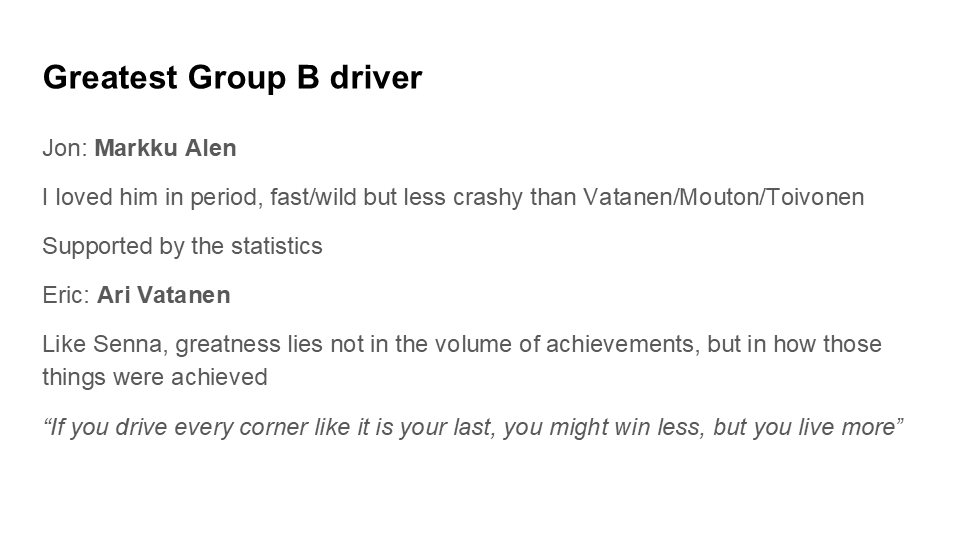

And then I’ll come back to that at the end of my presentation when we do when we do when we do questions and things. So let’s talk about that key question. Who was the greatest Group B driver? So for me, Marco Arlen. I loved him in period. He was [01:30:00] fast and wild, but he was less crashy than Vatanen and Mouton and Teuvenen.

And I’m was pleased to find that my gut feel was was supported by the statistics that we saw on the previous, uh, on the previous slide there. Now, Eric, I’m not sure Eric, if you remember, but in the pod car in the, in the pod that we did, you um, denied and couldn’t decide and mentioned some drivers that I haven’t even included on the presentation here.

Like Stig Blomqvist, who’s the inspiration for the top gear Stig. Um, but what you came down to was you thought it was your greatest was Barton and because you felt that like Senna. The greatness lies not in how many rallies you won or how many stages you won or how many championships you won, but the style in which you did it.

And, and I’ve a quote here from, uh, Vatanen, um, if you [01:31:00] drive every corner, like it is your last, You might win less, but you live more. And if there’s not a mantra to live by, if that’s not a mantra to live by, I don’t know, I don’t know what it is. So I am, I am

sorry for keeping Quinn waiting. I’m sorry. I’ve, uh, I overran the, uh, I overran the, the, the time there, Eric. Um, let me toggle back then to my, uh, to my, um, to my, uh, So my stats slide there, um, Raw has the most championships, Raw has the best wins to starts ratio, Arlen won the most events, the most stages, out of, yes, the most starts.

So, those are my thoughts. Thank you for listening everybody, and sorry for keeping Quinn [01:32:00] waiting.

Highlights

Jump to these markers for important points in the presentation.

- 00:00 Introduction and Schedule Overview

- 00:49 Special Presentation Announcement

- 04:22 Technical Difficulties and Presentation Start

- 10:32 Group B Rallying: An Overview

- 17:29 The Spectacle of Group B

- 22:16 Group B’s Influence and Legacy

- 32:43 The Monte Carlo Rally

- 36:21 The Safari Rally

- 52:21 The Rule-Bending Era of Lancia

- 53:52 Audi’s Motorsport Pedigree and the Quattro Revolution

- 55:40 The Evolution of Rally Cars: From Escorts to Quattros

- 01:01:55 Peugeot’s Game-Changing 205 Turbo 16

- 01:05:01 The Rise and Fall of Group B Rally

- 01:16:50 The Role of Co-Drivers and Helicopters in Rallying

- 01:18:51 Legendary Drivers of Group B

- 01:25:30 Conclusions and Reflections on Group B

There’s more to this story…

Go behind the scenes on the making of the Podcast version of this Presentation with the debate between Jon and Crew Chief Eric! Available now on Patreon. Stay tuned to The Motoring Historian on MPN to hear the full version when it becomes available.

Check out the Pod-version debate that started it all.

And some non-sequitor extras too!

Ari Vatanen’s Climb Dance

Climb Dance is a cinéma vérité short film, which features Finnish rally driver Ari Vatanen setting a record time in the highly modified four-wheel drive, all-wheel steering Peugeot 405 Turbo 16 at the 1988 Pikes Peak International Hillclimb in Colorado, United States. The film was produced by Peugeot and directed by Jean Louis Mourey. The record time set was 10:47.77

This presentation is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience.

Other episodes you might enjoy

8th Annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the Seventh Annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.

The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies.

The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center’s Governing Council. Michael’s work on motorsports includes:

- Walt Hansgen: His Life and the History of Post-war American Road Racing (2006)

- Mark Donohue: Technical Excellence at Speed (2009)

- Formula One at Watkins Glen: 20 Years of the United States Grand Prix, 1961-1980 (2011)

- An American Racer: Bobby Marshman and the Indianapolis 500 (2019)