On a plane some time ago I sat next to a VP of Marketing. We were returning to San Francisco, and she worked at a tech company. We discussed our work, and hence cars. I accurately guessed she drove a Lexus Hybrid SUV, which impressed her, but given the drift of her conversation – family/need the practicality of an SUV, had a Prius before, diligently studied consumer reports – it seemed fairly obvious to me. She aspired to a Tesla – this was a couple of years ago now, when Tesla was fully aglow with hipness, and no one had yet auto-piloted to their death using dodgy beta software – and asked me what I liked. I said Ferrari, and she responded by painting a picture of balding old men posing at the golf club desperately compensating for their fading masculinity. I tried to draw a line between new and old Ferraris, but my point was lost, so repulsive was the golf club posing. Given this, my snobbishness about the iterative design of Tesla seemed laughable to her.

I’ve wrestled with that since – for I am no golf club poseur – yet Ferrari represents just that to most people, most of the time. The Ferrari I love is a different machine, from a different time, driven in a different way. It is therefore spiritually uplifting to find others writing the same way – Bachelor:

“Standing beside one of these machines gives the viewer the impression it could pounce at any moment and devour anything in its way, man or man-made…..The horsepower and torque generated by the big V-12 was brutal, and the car’s response to that power – through the multiple disc racing clutch – was instantaneous and left no room for inept driver reaction. With 340bhp on tap in a car which weighed about 2400lbs at the curb, one could get into a lot of trouble at any speed if not careful. A further problem of Ferraris of this period was the weight distribution change between full and empty tanks. The 375 MM carried a 40 gallon tank, which meant a weight difference of nearly 300lbs between full and empty, behind the rear axle.”

“These cars were, and are, not for the timid or faint of heart. They required muscle, stamina, and full attention to every detail of driving to survive, let alone win a race.”

As editor of the Car & Driver, with knowledge and experience of an enormous variety of cars, it is significant that Ferrari were his choice, his passion in his private life.

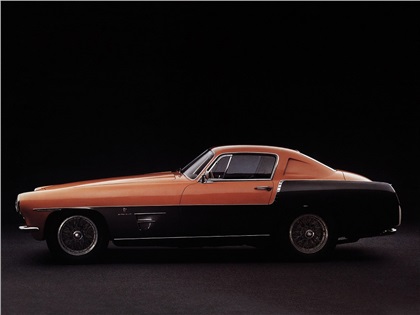

Through my work with the Blackhawk Museum– I am familiar with a 375 we display in the collection, S/N 0476, this 375 wears a Ghia body, offset by two tone salmon-over grey paint. Were I writing about the car for an auction house, I would describe it as “striking” and “period correct” but I personally find it hideous. For years, I couldn’t look at the car, and didn’t miss it when, for a while, it was absent from the collection. But it returned, and now I love it. The colors are pure GM Motorama, the styling American, and upright in comparison to Pininfarina and Vignale Ferraris of the period. Standing beside 0476 in the museum, I find myself thinking of “Metrorail”, one of my favourite Hot Wheels.

The Hot Wheels is a delicious confection – a Nash (or Austin) Metropolitan turned into a Funny Car Dragster; indeed 0476s charisma is similar – beneath the fairly upright, slightly gawky body beats the Lampredi V12 which powered Ferrari to his first Grand Prix victory, and defeated Jaguar at Le Mans without recourse to disc brakes. Inside the instruments are spectacular art deco jewellry. And this is what is so appealing about 0476: it is a pinnacle racing car, yet it also has all the fifties golf club appeal of any modern Ferrari, and in that we return to the Bay Area Marketing Manager, who saw only the pose.

I do not aspire to be a Ferrari owner – rather I aspire to be the kind of person who wrote this letter to Motor Sport, in early 1972:

FERRARI EXPERIENCES

Sir,

I cannot resist Mr. J, H. Thomas’s invitation to be classed as a “public spirited and knowledgeable member of the Ferraristi”.

I bought my 330 GT four years ago when it was already three years old and had done 24,000 mile it had been beautifully kept. I purchased it in Italy as, Living abroad, I needed l.h.d. and incidentally avoided the crushing English purchase tax. This amounts to around £2,000 on a new Ferrari which is of course reflected in the used market price.

The car has now done well over 40,000 miles which puts it into the category of Mr. Thomas’s enquiries. The old joke that one drives this type of car with a mechanic permanently in the passenger seat proved to be just that.

Parts renewed during my ownership have been points, condensers, a hose, a brake servo unit, steering pins and bushes, a dip-switch assembly and the routine brake pads (Girling), plugs and oil filters. The only serious mechanical trouble occurred last summer when the head gaskets had to be replaced—an expensive job. The silencers have needed welding and the door bases had to be treated for rust, though these were the only places so affected. The present set of very broad High Speed Cinturatos have done 13,500 miles and still have plenty of wear in them, which is just as well as the last time I was in England they cost £20 each. In my view, for a car of this age, the above list is not scandalous.

But spares are expensive. At least, they seem so to me, although not knowing the equivalent prices for English cars, I have no yardstick. I recall grunting sourly when charged £28 for a new brake servo and £10 for fitting, whereupon the garage foreman said brightly “Well, sir, if you will run a Ferrari . . .“ Spares are readily available for the older Ferraris as the design of the car (and that includes the impressively elegant body by Pininfarina) has undergone no radical changes in many years. Naturally, one cannot slip into the corner garage for them, but when I took my car to Maranello Concessionaires on the Egham by-pass for attention to the steering and brakes, they had all the bits in stock.

Petrol consumption is heavy, especially if full advantage is taken of that flashing performance—but what do you expect with 12 cylinders and three yawning double-bore Webers? Oil consumption on my car is negligible, but periodical oil changes of 18 pints a time fray the wallet at the edges…

Cool as the proverbial cucumber at auto-rouse touring at well over 100 m.p.h., it suffers from over-heating in prolonged traffic dawdling, although it is perfectly tractable, despite the poor steering lock often found in this type of car. Initially mine used to oil a plug or two, an ailment which gives the Ferraristi the chance to use the throw-away line “There I was cruising along at the ton on only ten. To cure this, I experimented with one or two well-known makes of plugs (including the one recommended by Modena) to no avail until a letter from K.L.G. put me on the right track and I haven’t had a mis-fire since. Ferraris seem to have a very individual reaction to plugs—another Ferrari owner I know swears his will not run properly except on a certain Japanese plug. Despite the special plug-spanner supplied in the tool-kit, changing plugs requires a certain dexterity.

If Mr. Thomas has read this far without being depressed and daunted, let me assure him that if he still intends a Ferrari he is in for a rare driving experience that is almost sensual in its appeal and may spoil him for other marques for life. I have not had such a thrill on wheels since I straddled my first motor-cycle, a D. R. Douglas, at the age of 14, and that, alas, was many years ago. Even after four years’ ownership, it still gives me rare pleasure to hear the distinctive mechanical sound of that V12 when It breaks into life.

If I seem unduly impressed by the Commendatore’s product, allow me to add that I did not graduate to it from some small box but a Maserati 3500 GT. That I bought, used and ran for four years as my policy has always been, on limited hinds, to buy a used quality car rather than a mass-produced new one. I get more fun out of my motoring that way. I hope Mr. Thomas joins the club and I wish him luck,

R. Hudson-Smith, Antibes, France

Link to the original article here