This article is one of a series written about cars in the Blackhawk Museum, as part of the Docent training scheme I have completed.

Motor racing and car sales have always gone hand in hand. No one understood this better than Henry Ford, who famously said “win on Sunday, sell on Monday”, perfectly summing up the relationship. In 1962, Ford boss, Lee Iacocca, then 35, dreamed of dominating the world of racing. This strategy has since come to be known as “Total Performance”. Within a decade, his dream was realized, with Ford success in Formula 1, rallying, and endurance racing, in addition to showing well in domestic US motor sports.

Motor racing and car sales have always gone hand in hand. No one understood this better than Henry Ford, who famously said “win on Sunday, sell on Monday”, perfectly summing up the relationship. In 1962, Ford boss, Lee Iacocca, then 35, dreamed of dominating the world of racing. This strategy has since come to be known as “Total Performance”. Within a decade, his dream was realized, with Ford success in Formula 1, rallying, and endurance racing, in addition to showing well in domestic US motor sports.

Legend has it that Henry Ford II was personally highly motivated to do well in endurance racing, such as at Le Mans. Ford had been in negotiations to buy Ferrari. The deal came very close to being inked in, but fell through, leaving “The Duece” with wounded pride. Shortly afterwards, Fiat acquired a large stake in Ferrari, a situation which remains to this day. Feeling aggrieved, Ford set out to beat Ferrari on their own ground. Formula 1 was important, and so were sports cars, and especially Le Mans, where Ferrari was enjoying an unprecedented six in a row winning streak.

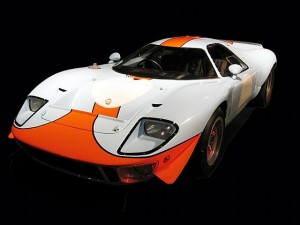

Ford approached three British based specialist racing car manufacturers with the brief to build a Ferrari-beater for Le Mans. This kind of work could not be done in Detroit, since at the time there was a “gentleman’s agreement” in force amongst the Big Three around not getting involved in the sport, and Ford lacked the in house experience of this necessary for this type of racing project. In the end, it was Eric Broadley’s Lola concern which completed the project, initially known as the Ford GT, later as the GT40, since the roofline was only 40 inches in height. After some teething problems, the GT40 won Le Mans, finishing 1,2,3 in 1966.

GT40s were campaigned by independent teams, as well as by the factory. One such team was John Wyer Automotive, JWA, based in Slough, England. Wyer’s background was first with Aston Martin (where he won Le Mans in 1959) and more recently with Ford themselves – he was team manager when Ford won in ’66. In 1967, Wyer returned with a new car, based upon the GT40 chassis, but lightened, and with a revised roof design, and said to have much improved wet weather handling. This car was known as the Mirage-Ford M1. The M1 used the standard Ford GT40 V8 engine in various capacities up to 5.7 liters. The highlight of the M1’s short racing career was without doubt victory in 1967 Spa-Francorchamps 1000 km. Only three chassis were built, and two were converted back to GT40 specification, so today only one Mirage M1 survives. It is likely that the Mirage M1s racing career was seriously truncated by Ford’s dispute with the FIA, the international motor-racing administration body. The FIA refused to recognize the Mirage as a Ford, despite protestations from all involved, meaning Ford could not take the credit for any racing successes.

Many changes were taking place in the late sixties in motor racing. Drivers were beginning to wear seat belts; hitherto, it had been considered safer to be thrown clear, rather than be trapped in a burning car. Tires were becoming much wider, and slick – without any tread pattern. These trends can clearly be seen on the M1. More than this, the streamlining of earlier years was giving way to ideas around downforce – using air resistance to press the car onto the track and achieve higher cornering speeds. Early in the 21st century, Ford decided to resurrect the GT40 as a limited-production retro-looking road car. Development engineers borrowed an original from a museum, and tested the vehicle in Ford’s wind tunnel. In the words of Ford aerodynamicist Kent Harrison, the car had “an incredible amount of front-end lift.” JWA were well aware of this issue back in 1967, when they fitted the small canard flaps to the nose of the M1.

How the sport was being financed was also changing. The Ferraris the GT40 sought to beat still wore Italy’s racing color, bright red. Wyer himself was familiar with the British Racing Green of the Aston Martin team. For 1967, the Mirage was the pale blue and orange of the Gulf oil company – and it was Gulf’s money which was behind the team. Indeed, many historians feel that it was this enormous financial muscle which Ford was able to bring to bear which was the key ingredient in the overall success of their motor sports program. Although the M1 was used for only a year, the relationship between JWA and Gulf led to some remarkable successes. Gulf –backed GT40s won Le Mans in 1968 and 69, the ’69 race featuring the closest finish in the history of the race. In 1970, JWA moved onto Porsche 917s, and the Gulf colors were forever immortalized by Steve McQueen in his movie “Le Mans”. During this period, JWA won three sports car world championships.

With the benefit of hindsight, the GT40 can be seen to represent the end of an era; up to this date, the sports-racing cars which won at Le Mans could, more or less, be bought and used on the road. Mildly detuned and softened road going GT40’s were sold, the advertising copy asking “Would you let your daughter marry a Ford owner ?” . Phil Rudd, drummer with Aussie hard rockers, AC/DC, owned chassis number 1078, a friend of his crashing it in London. By the mid-seventies, it was no longer possible to drive a car capable of winning Le Mans on the public highway.

Eventually, the GT40 would win Le Mans four times, even when it was considered uncompetitive and old, and it remains the only American car to ever win overall at Le Mans. More than this, Ferrari has never won Le Mans since, and now concentrates purely on Formula 1. If “Total Performance” could be summed up by a single car, it would most likely be a JWA Gulf-sponsored GT40.

Do you have a Facebook fan page for your site?

Not yet, but it is coming !!!!