On Ferrari Friday’s, William Ross from the Exotic Car Marketplace will be discussing all things Ferrari and interviewing people that live and breath the Ferrari brand. Topics range from road cars to racing; drivers to owners, as well as auctions, private sales and trends in the collector market.

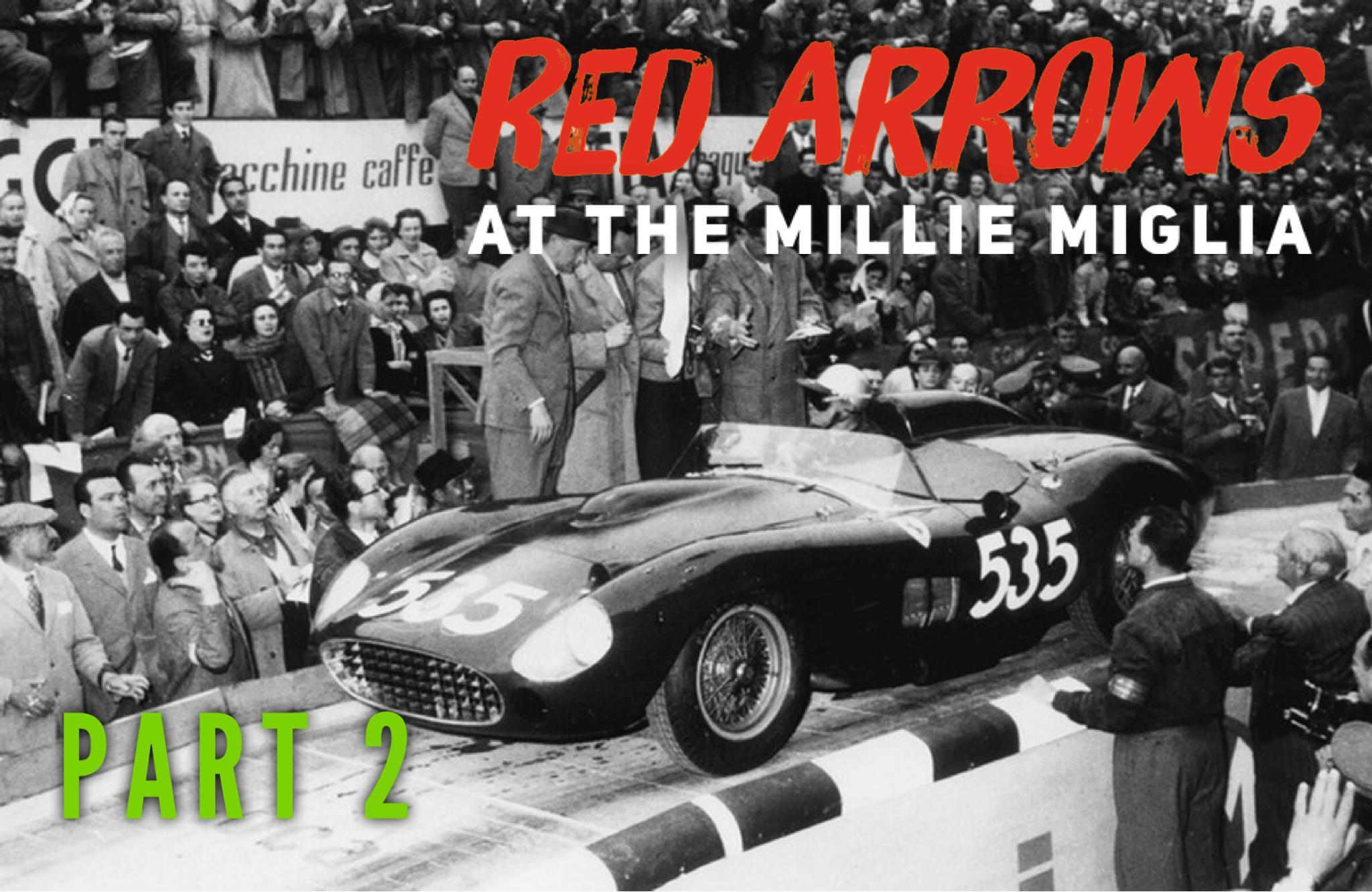

William returns with Jon Summers – The Motoring Historian & Crew Chief Eric from Break/Fix podcast, to continue the celebration of Ferrari and recounting the history of the Mille Miglia. This episode picks up from Part-1 at the end of 1953 through the catastrophic finale of the 1957 race.

Notes

Winning Ferraris mentioned on this Episode

- 1953 – Ferrari 340MM-Chassis 0280AM driven by Gianno Marzotto & Marco Crosara; Gianno Marzotto wins at 89mph

- 1954 – Lancia of Ascari with Marzotto 2nd, Biondetti 4th in Ferrari’s

- 1955 – Mercedes of Moss/Jenkins with Castelotti close behind. Record speeds!

- 1956 – Ferrari 290MM-Chassis 0616 driven by Eugenio Castelotti wins at 85.42 mph in the RAIN!

- 1957 – Ferrari 315S-Chassis 0684 driven by Piero Taruffi wins at 95 mph

Transcript

Welcome back to the Ferrari Marketplace podcast. We are back again for part two. Of our story of the millimillia, we have crew chief Eric on as our moderator and pundit that just, you know, likes to pipe in and ask some good questions. And we got Jonathan Summers, the motoring historian, is also participating again to wrap this thing up, take us home in the last 4 years.

If you [00:01:00] all remember, we ended up at around 1953, and we thought that was a good break point because as you get into 54, 55, 56 and 57, there’s some big jumps in regards to horsepower. The cars that are utilized and just the times, everything like that. So it was a nice break point. So we’re going to cover the last four years and John’s also going to touch base.

And we’ll discuss a little bit at the end there regarding what they’re doing now with it and how they brought it back. Not so much as a race, but you know what they’re doing with it now. So we’ll kind of talk about that a little bit at the end as well. But gentlemen, welcome back. We got part two going on here.

Picture it, Brescia, 1954. What is going on? Yes. Well, Lancia are in the house, aren’t they? This was the year of Lancia, or Lancia is the correct pronunciation, isn’t it? Well, I was struggling with the Italian pronunciation before. The other thing, I misspoke last time. I said that Lancia himself was gone. Of course, the father, Vincenzo Lancia, the racing driver from the beginning of the [00:02:00] 1900s for FIA, that guy was gone.

But his son, Gianni Lancia. Was driving this project, this return to motorsport for Lancia as a mark, you know, from the reading that I’ve done, Lancia were, were the team to beat in 1956 and quite interesting though, they were focused on formula one, the formula one car was taking a long time coming. They had the mechanical parts, so they felt like, you know, what.

We can put together a sports car team and the sports car team they put together, the cars that they built were maybe not, maybe similar in power to the Ferrari, maybe a little to the Ferraris of the period, maybe a little less dependent on the model. But my sense is that the Lancias went around corners better.

So, so the Formula One car was, I think, D20, was it the sports car that participated in them all was the D24 and the car was sufficiently good. You know, the, the best drivers went to them and 54 was won by Alberto Ascari. And that would be like [00:03:00] Verstappen winning the cannonball nowadays. I think that’s the right way to think about it in the Ascari was formerly a one world champion in, in.

52 and 53, I think those two years, but back to back for Ferrari. And there was a period there where he won nine Grand Prix in a row, which doesn’t seem that much in comparison to Verstappen, but in era when there were only six Grand Prix in a year. It meant that Ascari was unbeaten in Formula One for 18 months, so it’s this period that he makes the move from Ferrari to Lancia and does an event that he never really enjoyed very much, never really wanted to do, the Mille Miglia, and wins for Lancia.

What year did Lancia give all those D50s to Ferrari when they got an F1? What year was that? Right after Ascari was killed. Okay. It’s the spring of 55 and Ascari crashes the Lancia into the harbour at Monaco. In the Grand Prix, and then is at [00:04:00] Monza the following week. And William, you probably know this story.

He’s at Monza the following week. He’s a deeply superstitious guy, Iskari. Literally, if a black cat crossed the road, he would go and drive another way. He wouldn’t drive where the black cat crossed in front of him. Literally, the guy was that superstitious. He’s at the track. Castellotti or Villaresi or somebody was there testing a Ferrari sports car.

And Ascari says, can I take a couple of laps? Oh, the other thing is he didn’t have his lucky helmet. He went out and drove without his lucky helmet. Yeah, he borrowed. I can’t remember off the top of my head. He borrowed one of the other driver’s helmets that was there. I think it was Castellotti. I’m not sure, but I think it was.

Yeah, he borrowed his helmet. Yeah, because he didn’t have his thing. And I was thinking people are a little bit surprised that he did it because how superstitious he was. And I was like, this is kind of odd, you know, for him, and went out and did it, and that’s that. And rolls the car at the bend, you know, now it’s a right, left, right, isn’t it?

In those days, it was just a left hand kink, which if you think about it, was [00:05:00] one of the most challenging corners, probably the most challenging corner at Monza, and he rolled the car there. Yeah, this speaks to this whole thing of, you know, we see roll bars, disfiguring historic race cars now, and it can be quite hard to see.

I always feel like the Cobra is the only car that, you know, the little roll bar actually suits most cars. Terrible with the roll bar, but really when, when you think about it, the amount of drivers that we lost, especially in midget racing in the States, but really in open, we’re in, you know, in Formula One, the amount of drivers we lost, Vazzi, we talked about last time, you know, it’s a bang on the head.

The guy would have been fine had he had a proper helmet, and he certainly would have been fine had he had a helmet and a roll cage. But yeah, that was the loss of Ascari. That was, uh, spring 55, but you get the impression that it’s this grand, passionate gesture that with Ascari gone, we’re going to throw up our hands and we’re not going to participate anymore.

My understanding is that they were short money as well, that the effort to develop. The D 24 and the D 50, uh, completely, you know, spoiled them [00:06:00] financially. Not only that, they were also investing heavily in rally at the same time. So to run two different major disciplines of motor sport, that’s gotta be cost ineffective for them at that time.

So they had to make a decision. So without a talented driver, like Ascari in the ranks, you go to the other discipline of motor sport, where maybe lesser known, but it’s more affordable to run long term. Yeah. I mean, they reckon that Aurelia, wasn’t it? The B24, that was considered the finest road car of the period.

All the Formula One drivers wanted one in 53. You know, my own personal connection, you know, Mike Hawthorne, I grew up near where Mike Hawthorne lived. I have a lot of personal associations with Mike Hawthorne, you know, Hawthorne’s dad. Ran a garage named after the Isle of Man TT because he loved motorcycles, but he sold Lancia.

We sold Lancias and then Jaguars, but he was a committed Lancia guy. Absolutely loved Lancia. Did Leslie Hawthorne, but we’ve digressed here somewhat, haven’t we? [00:07:00] So for the Mille Miglia in 54. Ascari is in one of the lancers, but Ferrari is still able to field a pretty strong team of what, William, Ferrari 375 pluses?

Was that what they were running then, or was it still 340s? They had 24 cars, 24 Ferraris that registered. Three or four did not even start, and then obviously had a large portion of retired, but you had the 500 Mondial. You had a 250 MM, you had 375 also in there, not many of them, MM and a plus, 212 export, 16 MM tried and true at 212 inter, 340 America, 250 Monza.

So, I mean, it was kind of a, again, a scattering. Of different models that Ferrari had produced. Wasn’t the Mondial a four cylinder? Wasn’t that car that RM had? Just this, that was like the twisted up wreck. And they were like, literally, it was a, it was a twisted up tin [00:08:00] can. And they were estimating 1. 2 million.

And you rolled your eyes. And then it made like 1. 9 or something. Wasn’t that a Mondial? Yes, it was. Yeah. And well, not only twisted up, it was burnt. It was in the fire. That’s where people are kind of rolling their eyes and, you know, people just couldn’t get it, you know, understand it. But when you start breaking down, and again, it’s going to be how someone views it, because is it the actual car?

Hey, they take the chassis plate off it, put it on a whole new car, which you’re going to have to do. I mean, and maybe they’ll save a couple pieces off that chassis just for originality reason to say it. But whatever they make out of that’s going to be completely brand new car, but you know, they try to justify it, say, well, here’s what one complete restoring goes for what now?

It’s like, well, because if memory serves me, I mean, they have the engine and transmission for it to to put in there. Oh, I didn’t know that they can put it all back together. But. Is it really the car? Oh, I think so. I thought there was nothing. I didn’t realize there was the engine and transmission. I think if there’s the engine and transmission, I think the bodywork, that’s [00:09:00] just the dress on the beautiful woman, isn’t it?

That’s what Ferrari used to say. He was all about the engine. If you’ve got the engine, then that’s the real thing. I was going to say about the whole car. You see, I feel like it would be like a continuation Cobra. The great thing with a continuation Cobra is it’s just like the real thing, but you can go out and drive it just like they did in period.

And if you wrap it around a lamppost, well, that’s a sad day, but we’ve not thrown away a piece of history. Whereas were that Ferrari Mondial. As it had raced in the Mille Miglia. You could never do that. It would be destruction of a work of art. But if it’s something which has just been knocked up in a workshop 10 minutes ago, that’s exactly the same as the original was.

Well, that’s awesome. You can go to Goodwood and you can cosplay that you are one of the Marzotto brothers. I mean, it’s the best thing in the world. Oh yeah. I said, there’s an ask for every seat. So it just depends on what someone wants to do. Yeah. I mean, it opens a ton of doors for someone. Getting into events and everything.

And [00:10:00] again, I don’t know if it’s, someone’s going to get it at a value price compared to like a real original one. I say never wreck cause they all pretty much have been wrecked at some point to what extent, but you know, it’d be interesting to see in three, four years when the car is done. I mean, that’s gotta be a minimum, if not maybe five years for them to restore that car, unless someone just goes whole hog.

Now you’re talking basically building a whole new chassis, all new metal work. And then you got everything else. I mean, you have your engine and trans you dropped in, but then you have everything else and it’s. And it’s not like you can buy, find NOS parts to put on that thing to what extent, I don’t know, it’ll be interesting to see where they get that thing done because it’s going to make a splash because everyone’s going to know where that car came from and what they started with.

So it’s going to be interesting to see and some people are going to knock it and say, no, I think Joe, it’s not even a real thing. Everyone say, well, no, it’s got the chassis plate. Hey, all race cars were wrecked back in the day. And you know, how many cars actually out there still have their original chassis, blah, blah.

And there was, um, like a big argument and court thing on that 935, [00:11:00] uh, was the Kramer Porsche ever was, uh, about which one was the real lungs. They both had the same thing and, you know, went to the courts and everything about it. You know, so you have a lot of that. And it’s unfortunate, but some people play that game.

Well, we should touch on this, shouldn’t we? Because isn’t the one Ferrari chassis number that there are three iterations of? Yeah. But for people who don’t understand this, it’s really hard to believe. But fundamentally, I think what happened was the car crashed, was wrecked. Then. It was broken up, and one person had the engine and one person had the body, and then when old Ferraris became multi billion dollar cars, both people built a complete car, replica, original, whatever you want to say, built another car around the bits that they had, but for there to be three, there had to be some additional knowledge.

Wrinkle in that. Do you know what that wrinkle is? Will you? This might be similar to what happened to James Dean’s 550 Spider and we had Lee Raskin on a [00:12:00] couple seasons back who’s the world’s expert on all those cars and the way they did it in that case was Part of the chassis supposedly went on this national road show for the highway safety commission, but that was the body and the engine got sold to somebody and that has its number.

And then the transaxle had a matching number. And so the car got sort of split up in three ways and there’s rumor where his engine ended up where the transaxle. was found under some guy’s porch and all these kinds of things. So it’s not unbelievable that this would have happened to a Ferrari as well.

And again, goes back to what Trevor Lister was talking about in the episode that aired earlier this week about how these numbers don’t match. And we should really rely on the engine number more than anything else at the end of the day. Yeah, in my opinion, I agree that’s your beating heart of the vehicle, you know, and that’s why some manufacturers, especially back in the day is that was their definitive, which car was, which was by the engine and transmission.

It wasn’t, it had nothing to do with the chassis number. It was like an afterthought, but their reasoning was no, Hey, whatever [00:13:00] that engine did, that’s your, that’s the car back then because accidents, whatnot, and things getting rebuilt, obviously, because the price of these things, there’s a lot of shady people out there that, you know, are going to do whatever they can either a Somehow, some way they got their hands on a chassis plate number, or they, um, you know, have one reproduced or something like that.

And especially this day and age, you know, you can really fake something really good in regards to patina and whatnot. You know, you’re always going to have an argument with someone, you know, the person that owns owns it is always going to say, no, mine’s the real one. The other person owns it’s going to say theirs is the real one.

If it turns out that you don’t have the real one, unfortunately, because you’re gonna take a hit financially. But, you know, you could bring in five different experts, get five different That’s really what it’s about though, isn’t it? It’s really about money. It’s really that people only built all these cars up when they were worth lots of money.

Yeah. And now the argument is, is that mine’s the real one because it’s not got the engine. And you’re saying, no, no, mine’s the real one because it’s got the chassis. And then the bloke that had the paperwork all along and [00:14:00] had one wheel left. Cause when his grandfather sold the car, he didn’t give the title.

He like lost the title or something. Cause that’s the kind of thing that happens, isn’t it? With it. That’s how it evolves. Oh yeah. There’s a whole world of fakes. There’s a factory in Russia somewhere, which is making fake. Mercedes 300 SLs that are being passed off as real. That was something somebody told me.

Uh, that was like a whisperings on the lawn at Pebble conversation I had a couple of years ago now. I don’t know if that’s still going on, but a couple of those cars had come onto the market. And whilst we’re on the theme of these sort of, is it fake? Is it real? Are you guys aware of, is it Pura Sang? Yeah.

Workshop in Argentina who will make you a replica. They’ve done like Tassio Nuvolari, Achille Vazzi, Zagato body style, Alfa Romeo 1750s and 2300s and that kind of stuff. They’re famous for Bugatti Type 21s. They’ll also build you an Alfa 8C if you [00:15:00] really want it. I’ve seen them with the Alfa. They just started doing Bentleys too.

Bentley blowers. You know, you have a lot of these companies out there and, and I think Pursang, Pursang, however you pronounce it, P U R S A N G. You know, they’ve been at it for a while. You know, they were building replicas, but I think they really kind of made their stamp in the world in regards to they started doing the Bugattis.

And they’re not cheap. It’s not like you’re talking 89 grand. I mean, these are half a million, if not more. And they’re supposedly tool room copies in essence. Of what, you know, the originals were. So I mean, basically as close as you can get, and I believe the FIA has finally kind of, I want to say caved in or basically said, well, yeah, you can get FIA historical papers for these, you know, and run them because obviously the value of real ones is so high.

People won’t bring them out and run them on a track. People want to see these cars. So they’re kind of like, all right, well, let’s just give them the papers and do it and be able to run it. It’s kind of like there was a proliferation of these companies doing it. But then all of a sudden you had a lot of these manufacturers all of a sudden pushing back in regards to trademark and all that kind of [00:16:00] stuff in regards to what they were making.

Because it can knock on what and the value and everything like that. You know, think of Ferris Bueller’s Ferrari. You know, that thing’s actually in recent years, that thing’s been jumped around a few times regards to sale wise. Me personally, I don’t put any value with something that’s got like a movie problem on it.

So that I could give two shits if it’s been in a movie or not. Only person I think I put any kind of, I guess, weight to it in regards to Bao is maybe Steve McQueen, but not as much as people do. I mean, I think it’s obscene what some people play just because they say, Oh, Steve McQueen owned it four owners ago.

Didn’t know he wasn’t the last owner. That 911S that he has at the beginning of Le Mans is more interesting than the 917 that he drove in the movie. Yeah, exactly. You know, stuff like that. So, um, it’s kind of an interesting world getting into in regards to historicals. You have it where people, these owners, don’t want to bring those cars out and run them on a track with anyone else.

They might do it by themselves and do a solo run around or something like that, but they’re not going to race in any of the historical races just because of value. So I think the FIA is kind of caving in regards to authenticity and saying, Look, we get it. But there are [00:17:00] museums out there that do exercise their vehicles.

Two of them come to mind. One of them is the REVS Institute in Florida, and the other is the Simeone Foundation in Philadelphia, where they will take these one of a kind, basically priceless race cars, And exercise them on track or in their parking lots or whatever. Have you? Yes, exactly. Well, Sydney does it once a month, isn’t it?

Like every, the third Saturday or something of the month. So anyone, Hey, if you’re in that area, go check it out. Look it up. Awesome museum, the collection, unfortunately, Dr. Samuel passed away recently. All those cars in there are just, you can almost say priceless because all of them. Or a winning car from a race, either Lamar, Daytona or something.

So they all, they were a winning car. That was kind of his prerequisite. So he’s got some spectacular machinery down there and I highly recommend if you’re ever down in Florida over by Naples. Go to the Rebs Institute. It’s a phenomenal museum. The people are super nice. It’s a great place to go and spend three, four hours.

The docents there that walk you around, know this stuff left and right. They’re super nice and they take you around [00:18:00] and answer any questions you got. So I highly recommend the Rebs Institute as well. You know, they do a phenomenal job. Not people, I would say, aware of it, but I don’t think they know, hey, it’s actually a museum.

You can go there and check things out and, and see what they got going on. But, you know, I definitely highly recommend. Both of those, if you’re ever in those areas, definitely hit those up. So now we’re going to get back to where we’re supposed to be at in the middle. Amelia. So 1954, there’s a lot of things going on in the world of motorsport.

And we just talked about a scary death and there’s some other tragic deaths in that year. But what’s interesting about that is you mentioned where he wrecked in Monaco. This. repeats itself with Bandini in the exact same spot a couple of years later. And we can unpack that on a totally different episode.

But I want to go back to something, John, you talked about in the first part of this discussion, which was Biondetti. He was 56 years old. He’s pretty sick. He only has a couple months to live. 1954, Mille Miglia was his last race. And in not that fast a car. He finishes fourth, [00:19:00] and I reread the Mike Lawrence account from the Brooklyn’s book that we talked about before.

He says that he thinks that had he not already been dying of throat cancer, he probably would have performed much better than he did. He could have even won really a remarkable drive and remarkable performance. So is there anything else that we should highlight from 54 going into 55, or do we just jump into the next year when Mercedes shows up to shake the tree?

You were right to highlight B and DE’s fourth. The other thing that, that we should talk about is that the fact that, so there are four Marto brothers and at different points all compete and feature significantly in in the Milli milia. Of course, Giannino wins twice. Is it Vittorio? I’m not sure that the V Marzotto finishes second in 1954.

I think in one of the earlier years we talked about Paolo was super competitive from one of the lower classes. I want to say had a race, really close race, one year with, with [00:20:00] Musso, who we know who went on to be a Ferrari Formula One driver. So yeah, so, so we should highlight the contribution of these four super wealthy brothers, all of whom compete in a meaningful way in the Mille Miglia at different points in these last 10 years of its, of the Mille Miglia’s run as a proper competitive event.

I guess the other thing to say about 54 is the, is the passing of Tazio Nuvolari. And because Nuvolari’s died in the last year, and because everyone in Italian motorsport has such enormous reverence for him, the route is changed to pass through his hometown, Mantua. And this gives rise to, and they also do a special little prize.

So the run from Cremona, where they made Stradivarius violins to Mantua, and then on to Russia. There’s a special prize for this bit at the end. I know that bit of the course quite well. Many years ago, 2004, I rented and [00:21:00] rode and a pre or RSV millet. I rented it in Milan and I did the Futa and the Raticosa.

And I also did this, like, Novellari Grand Prix bit. I visited the Novellari Museum in Mantua. It’s really worth doing if you’re there. It’s a nice part of the world. But those final sections, it’s super, super fast. And the countryside is very, very flat. And I was passed by another guy riding an RSV Millet and he did the Follow Me.

And I really did a brain out with him. It was like a Sunday evening and it was a two lane road and there were cars on both sides, but we did that European thing where you put the bike on the white line and then you can weave in between the cars. Well, this guy was really good and we ran. At Mille Miglia speeds in those moments, I really felt the Mille Miglia and the spirit of Nuvolari.

So since you bring that up, what people may not realize about the importance of Nuvolari, and there’s not many people left of that [00:22:00] generation that would have been our age when Nuvolari passed away, but he was the Ayrton Senna. of those times. He’s regarded in that similar way in Italy, a national treasure and all those kinds of things.

So I want to draw that parallel so people understand the importance of Nuvolari’s passing. You know, we, we tend to exist in this world where we say, Oh, who is the greatest driver of all time? And then we think, how can I compare Mark Marquez with Vincenzo Lancia? I mean, the answer is You can’t. So, so we narrow it down and we talk about the greatest Formula One drivers.

And then when we do that, it’s quite convenient because it means that we can forget about all these pre war guys like Rossemeyer and particularly Nuvolari. But Nuvolari for his whole style, for the arriving at the corner sideways, for the whole, like, when the mechanics taking too long at the German Grand Prix, he leaps out of the car and yells at the mechanic.

It’s this pure Italian. Passion. Nuvolari is the personification of Italian passion. He’s the [00:23:00] personification of the pissed off short guy. And we talked a little bit about him last time, but really we can’t underscore how much the loss of his sons turned him into. Somebody who looked for death on the track.

He did not want to die in bed. So when he stepped into that, she’s telling 1948, although it was 48 and 49, 49 was the Ferrari that fell apart and the racing on the bag of oranges and lemons and. Ferrari weeping ’cause the car’s not strong enough. Although Naval LAI’s heart is big enough, this is NA’s special place in all of Motorsport, not just Italian motorsports.

So I would say, and I say this as a Sen fan, I would say bigger than Senna because Naval is Ri Vartan and Sena, he’s Sebastian Loeb and Michael Schumacher. I dunno if you guys have seen it, but anyone out, you guys listening, there’s a great magazine called Taio has been out. I think the guy like. 12, 13, I mean, fabulous magazine.

Really nice. [00:24:00] We had a chance to check it out. What Marzotto and being daddy, which was interesting, especially being daddy is they both ran solo, they didn’t have anyone riding with them. No, no mechanic or anything like that. No. And you have two contrasting cars, Marzotto coming in second, driving the Mondial, which is a four cylinder.

And just for nerds sake, it’s chassis. Oh, four Oh four MD. But then. Being Daddy, you know, he’s driving a 12 cylinder, 250mm. And just for the nerds, 0276mm is the chassis number. So my understanding was, though, that V12 made a bit more power, but the 4 cylinder was more reliable. So the feeling was, Ferrari liked entering both, felt like hedging his bets.

That was the thing about that horse. I mean, I think it’s like 170 horsepower in that range like that, but the torque, it was like, as someone said, it’s like pulled like a tractor. But reliability wise, that thing was, you know, I would say bulletproof, but it was, you know, obviously you have less moving parts, that kind of stuff, but it was very, very reliable.

So, and that’s why he, you know, obviously Enzo always favored the B12, but it’s like, no, hey, for reliability [00:25:00] wise, whatnot, I’m going to also hedge bets and put these cars in there. And those four cylinders were actually very, very successful throughout, you know, the years that they were campaigning them. If, if you have a chance, look it up and try and hear, and listen to hear one.

And it’s got a very unique sound in regards to a Ferrari. They’re a screamer. They’re great engines. And I think they didn’t build four cylinders all that long. I want to say it was only made for like six or seven years or something like that they did them. And then again, obviously everything’s dictated by regulations for the series as they wanted to race in.

And what was their best bet in regards to? But then having the best car, you know, so everything was kind of built around that kind of interesting to see those two contrasting things in it. Cause you got 12. So I was reading about that co driver thing, right? Previously they had to have a co driver then later on it became superfluous and kind of dangerous.

So Fangio. never has a co driver because he had an accident in one of the South American road races he did years ago [00:26:00] before the Second World War, and his best friend was killed in the accident, and so he never wanted the responsibility of driving with anybody else. My sense is a scary So I don’t, I can’t remember exactly which year it was, but a rule did come in one year that you no longer had to have what they used to call the riding mechanic, or what we might call, you know, the co driver or the navigator.

Now we’re just about to talk about 1955 here. And it’s worth saying that. In 1955, Stirling Moss won with Dennis Jenkinson, and the defining factor is that Jenkinson is there alongside him, helping him with direction. It always kind of made me scratch my head, because you would think that that’s just something that, you know, would just be common sense, that, oh, we’re driving this long ass race, thousands of miles, twisting turns and whatnot.

Why wouldn’t you do that for? I just, I was amazed that no one else had done it before. We were talking about open cars [00:27:00] and covered cars and co drivers a moment ago from Mike Lawrence, writing in those Brooklyn’s books, talking about Braco saying that co drivers had largely become superfluous. They were only doing things like occasionally helping change a tire or in Braco’s case, supplying him with brandy and cigarettes if they were foolhardy enough to ride alongside him.

And you know, that’s what it speaks to, right? Is that it speaks to, in Braco, you have how the sport was and in Moss, you have how the sport is going to be. How the sport is going to be is professional and planned. It’s a factory team who’ve arrived with a T car and a Mercedes 300 SL, and you do laps of the course before.

And when Moss and Jenkinson wrecked a 300 SL by crashing it into the back of a farm cart, they went back to Stuttgart expecting Neubauer to yell at them. And instead he just gave them another car and said, we’re really pleased you’re not hurt. That was how Ben’s approached winning the Mille Miglia. [00:28:00] Now, a word on these pace notes.

There is a museum in the central coast of California, not far from where I live. It’s called the Estrella Warbirds Museum and it’s mostly planes, but then bolted onto it is this sprint car museum, which is one of the best collections of sprint cars I’ve ever seen. Within that sprint car museum, in a cabinet is a roller.

A map of the Carrera Panamericana that was drawn up by Bill Strop and Johnny Mance. Really? Yeah. When Lincoln arrived with a whole bunch of money and was like, let’s win the Carrera, they went to that old California hot rod at Bill Strop and Strop built the Lincolns. Strop and Mance developed this system of a roller map.

Now, one of the other guys on that team was John Fitch. John Fitch, an American fighter pilot, was also on the Mercedes team, and I believe it was John Fitch, in conversation with [00:29:00] Dennis Jenkinson, that introduced the idea of the map. So Jenkinson is Moss’s co driver in 1955 for Mercedes, and he is a really interesting character.

He is small. He is English, he has a big bushy beard, he lives in a house with no water or heating. When he was given a Ford GT40 he waited until Christmas day and then he went out and drove it at 160 miles an hour on the public highway because nobody else was going to be out on the road on Christmas day and he wanted to test the car properly.

That’s Dennis Jenkinson. He was world motorcycle champion in the early 50s and I feel like he needed to do that. Because in the war, he’d been a conscientious objector. He didn’t believe in the war. So in order to escape being branded as a coward, I think he did that motorcycle racing afterwards. And you can see just what a push against the system kind of a guy he was.

Most people would, you’d been afraid to sit alongside Sterling [00:30:00] Moss as far as. Jenkinson was concerned it was the best seat in the house to watch the best driver compete in one of the most exciting motor racing events you were ever going to participate in. So they drove the route, they made what they called the loo roll, the toilet roll of this map.

And it was by being able and, and this is the example I always think about when approaching a crest at full speed, 175 miles an hour in the 300 SLR, Moss knew that he could just hold the throttle flat because Jenkinson was being like, I know it’s straight over the crest. Everybody else, they’re shitting themselves.

Do I need to lift the throttle? Does the road turn left or right over the crest? Now, Braco. to roofie they knew the road no issue for them but for the foreigners it was hard and mercedes benz with the planning and with dsj’s map making and then with sterling moss’s sheer balls out commitment in practice moss said to [00:31:00] dsj you know i’ll probably be a bit afraid i’ll probably lift a bit anyway In the race, no chance.

In the race, it was pedal to the metal over the rises. At one point, the car took off and DSJ in the report that he wrote about it afterwards from Motorsport, if you’ve not read it, you need to, it’s the be all end all piece of motoring journalism. Whilst the car is in the air, the two of them meet eyes and then the car lands and they carry on.

This is a 175 miles an hour on a narrow crown piece of. Italian road. I mean, just stop and think about what that, the implications of that do that route, like 10, 12 times, but I know they did it a lot to get the notes and everything. And now that they do it, not only the notes, but they had their hand signals down and do it, but didn’t they go do it like 10, 12 times?

How many times do you think somebody like Tarufi drove from Brescia to No. Or Martin at, uh, bologna or Bologna. The Italians drove the route all the time. Yeah, [00:32:00] all the time. The, the only way you were gonna be able to commit was by having a driver who was ready to be as brain out as moss. And remember right in the early parts of Ds J’s report it’s called With moss at the mil, mil otti passes.

Moss early on and on the approach to Florence Moss slides the car, hits some hay bales and damages the front of the car. So Moss is trying like Duke’s a hazard hard and Castellotti passes him and DSJ talks about Castellotti using all the roads like being up on the sidewalks. And this is what I really want to fix in people’s minds is that when you look at the film on TV, it’s always in town and the cars have always slowed down and it’s the control, or it’s like a left, right zigzag in town where loads of people have stopped.

And that’s where the camera is. Cause there might be action there. If you watch that shell movie of the 1953 film, there’s a couple of clips where the camera car is out on the road and you can see the Lancey is [00:33:00] passing at like 150 miles an hour. That’s the real millimillia. That’s the sense of speed. And that speed combined with the wildness of Castellotti, this is why the attrition rate was so enormous.

I mean, it’s just the whole event just boggles the mind with the speed and the danger and the way that particularly the Italians drove. Wrapped up inside of your enthusiasm for 1955, John, is something that William alluded to several times, is the technological jumps that were happening From 53 to 54 to 55 to 56 and so on.

And it’s very, very clear, especially between 54 and 55 hop speeds. You’re adding at least 25 mile an hour. The horsepower is going up and the average speed of the race jumps significantly from 87 miles an hour to almost a hundred miles an hour on average. That is huge because it was dry. It was dry. So Moss has this clear run.

I think on this performance thing, I think the [00:34:00] cars gained about five miles an hour a year. If you think from 47 to 57, if you say five miles an hour a year over that decade, that’s 50 miles an hour. And that seems about realistic that would lift us from 130 or 140. to 180 or 190. I think there’s an incremental increase here.

I think that Moss’s speed was due to it being completely dry. It was fairly dry Ascari’s year. 56 and 57 it was wet for a lot of the event. 56 it rained. Absolutely throughout. Yeah, I should just say as well. The other thing that I think is interesting about Dennis Jenkinson’s account from a Ferrari perspective is, is that Castellotti’s Ferrari had the legs on the Mercedes out of the towns, but once the cars were up to cruising speed, the Mercedes could hold the Ferrari.

So what that speaks to for me is that Mercedes had really focused on making sure the gearing and all of [00:35:00] that was right, whereas Ferrari had. Put a giant engine, super powerful engine. And then maybe the back axle ratio was right. And maybe it wasn’t, and maybe the gearbox would hold together. And maybe it wasn’t, it was just, you know, Ferrari, it’s all at the altar of the V12 engine.

It’s funny. He’s speaking about engines, the second place guy, they’re actually running six cylinders that were the ones that were more, I guess, a prevalent in that race and, you know, jump wise horsepower wise, or you’re going up, you know, it got up to 280 horsepower now in these six cylinder cars. They had the 118 and the 121 LMs that they were running in that race.

Now your 118 was a 3. 7 liter and your 121 was a 4. 4 liter, you know, a little more power and whatnot in the bigger motor reliability wise, kind of hard to say, but it was three of the guys that thought they were running the 118s with the 3. 7 liter and Ferrari actually, unbeknownst to the owners of drivers of those cars actually.

Stuffed in the bigger motors into it. So they’re thinking they got this 3. 7. They actually got the [00:36:00] 4. 4. So that’s kind of funny. When it comes to Ferrari again, pulling the, I would say old switcheroo on some of their drivers and the owners is stuff in the bigger motor without telling them. You know, I don’t know the psychological reason why it’s whatnot.

Why you wouldn’t tell them you’re not talking a huge jump, but performance wise, obviously it might seem to help a little bit, but again, you know, you got single person driving the car. And you got these six cylinder cars that are actually, you know, up at the front, you know, not only, you know, uh, Moss and Jankstiel winning, second place was another Mercedes with Fangio driving it.

And he was like almost 30 some odd minutes behind them. Now it has to do with pace notes or whatnot. But as we all know, Fangio wasn’t too bad of a driver. My sense having studied Fangio is that he did not care. I feel like the only time he tried in the Mille Miglia was in 53 when he was coming back after his bad accident and he really wanted to prove to the Italians that he still had it.

If you look at Fangio’s performance, It, the South American road races that would be [00:37:00] like five days over the Andes when the car stopped overnight, you were still allowed to work on the car. So he would like work on the car all night and then get up and drive and drive. You know, DSJ said about Fangio that after those South American road races, the bumps of the Nürburgring held no fear for him.

And I feel like. He looked at the Mille Miglia with those giant crowds and the distance that wasn’t that vast in comparison to what he’d done in South America and just thought, this is not an event that I want to go balls out. It also shows the power of cocaine. I mean, the coca leaves, right? Okay. And, and you say that, right, Eric, this is, this is, I’m pleased we touched on this because yes, he used to chew these coca leaves and it’s quite well known.

And I feel like I want to chew them as well and kind of get a sense of, is it. I do want to do that part of motoring adventuring to see if they have any effect or not, but Moss said in period that before the race, Fangio had said [00:38:00] to him, have these little pills. They will help you with the race. According to Moss, this was the only time this has ever happened.

He did take them after the race. He drove the car back to Stuttgart to show the directors of Mercedes of Daimler Benz. So that’s, he did the Mille Miglia, won it at record speed and then drove the car. From Brescia in Italy, across the Alps, and all the way back to Stuttgart, northern Germany. I believe we call those performance enhancing drugs now, John.

Dexedrine was the speculation that I’d had. Frankly, pilots in the Korean War, if anybody was a fighter pilot in the Korean War, probably whatever they were giving those kind of pilots, because it was dexedrine for the pilots in Vietnam. I don’t know what it was for Korea. I assume that there was experimentation with performance arts and drugs in, in career as well, but I don’t know for sure.

What I was going to say is, is that, you know, just to speak to Moss and Jenkinson, they participated in [00:39:00] 1956 and 1957. And in 1956, They slid the car off the road and would have fallen down into like a hundred foot crevasse, but it was stopped by a single tree. They got out of the car and were standing at the side of the road.

And when Fangio came by, he stopped and offered them a lift. Now that is proof to me of Fangio’s attitude to the Mille Miglia. He stopped in his sports racing Ferrari that was going to win the race. He stopped and said, are you guys all right? Do you need a lift? Actually, they walked to the local railway station and went from Or does Fangio’s behavior speak to the fraternity and camaraderie of drivers in motorsport?

There’s another way you could probably take that particular position, right? Well, there is, because in those South American road races, if you saw somebody at the side of the road, you would stop and help them. And Fangio’s great rival in those South American road races were the Chavez brothers. And there’s numerous incidents of the Chavez stopping to help Fangio, and him [00:40:00] stopping to help them.

And this is, is really Crazy. It would be like Verstappen seeing Hamilton struggling at the side of the road with a flat tire and not just helping him back to the pits, but getting out of the car and helping him change the tire, even though the others are catching up. But you know, these South American road races, they would do them in these like Fangio’s car was a 40 Chevy and they would cut the fenders and then like put the suspension up high.

So it looked like Baja. Trophy trucks. Look, now it had that kind of stance and high suspension and all of that because that was what it needed to do. So in that kind of environment, if you saw somebody off the road, you stopped and helped them. So I’m sure there was an element of that, but I just feel like you can’t see Castellotti, Ascari, you can’t see them stopping.

You think Braco would have stopped to see if the young, young English pup was okay. Only if he ran out of brandy. I was going to say 57, just to finish off Moss and Jenkinson at the [00:41:00] Mille Miglia, 57, the Maserati 450S gets put together right at the end, right before the, you know, we’re about to kick off, the race is about to start.

And the 450S is an awesome looking car. I would say probably 190 mile an hour car, certainly 185. Mile an hour, really an awesome piece of kit. As we know, at the start, it’s these long straights from Brescia over to Ravenna and then down the Adriatic coast. Well, before they’ve even got to Ravenna, the first piece of heavy braking, the brake pedal broke off.

Well, that’s not good. Now I just need you to stop and think about that. Literally you’re about to do the milling, but you’ve hit the brakes. The brake. Well, they were so mad. They drove the car back. They were ready to fight the Maserati mechanics. They broke down in tears. And you’ve got this contrast then between the planning of Mercedes Benz and this sort of slapdash, can’t even weld the brake pedal properly, of Maserati.

Big contrast. I think we’ve stumbled [00:42:00] backwards into 1956. So how does this story continue? We know it’s a rainy Mille Miglia in 56. Yeah, we’re back to V12s in the Ferraris. We’re at a pivot point, aren’t we? Because Castellotti wins in, in a time which is really pretty astonishingly close to Stirling Moss’s time, yet in rain throughout, in a car which is undamaged.

Which is remarkable, right? If you think about Moss had two or three offs, which Jenks documents, you know, we know Verrazzi won in, in 51 with a car that, you know, it looked like a NASCAR that had been beaten up, you know, it really carried some heavy damage and contemporary reports make play of the fact that Castellotti won with the car completely undamaged.

And some of the reports will even suggest he had this sort of. unbroken run. I think actually in the race, it was pretty competitive to Rome, but by the time he got past Rome, which is about the halfway mark, by the time they got past Rome, Castellotti was really very comfortably in [00:43:00] command. You know, Moss and Jenkinson talked about how wild the guy’s driving was.

The Italians talk about it in a very poetic kind of a way. The previous four, Mille Miglia, Castellotti had not finished. So, again, we’ve got this sense that it’s pedal to the metal, even in the thrashing rain here. So, hats off to Castellotti, and it’s Castellotti’s coming of age. I think that’s what we’d say is that for Ferrari, Ferrari took notice of Castellotti.

After his Mille Miglia victory, Fangio, who was on the Ferrari works team, just briefly at that time, requested that Castellotti drive with him in all sports car races, which is a huge compliment to Castellotti. Of course, he’s killed at a Formula One race at the modern water drone, just a. Few years later with him and, and with Musso disappears.

This whole tradition of Italian racing drivers, the pre-war guys, the Burnetts to [00:44:00] Rufi, Farinas fa Jolies Villa. There’s loads of them that we see represented in the milli mil. Now by the late fifties, these guys are kind of dead or retired. And, you know, there’s only Tarufi left. And Castellotti is one of these new, young generation.

And that’s illustrated by the fact that he came up through cars, like a modern racing driver, like Sterling Moss did. Braco cars as well. Whereas everybody else we’ve talked about came up through motorcycles. Castellotti, different from that. You know, if you look at the times, You know, the time that he won in, I mean, it was, it was about 90 minutes.

So an hour and a half, roughly, you know, behind what most of the year before, but people don’t understand is, you know, you look at the race itself and people say he would have beat Moss’s time if he had the same conditions that Moss had, he was just absolutely flying. But obviously with the rain, the weather and they really hampered his efforts, but they were just saying he was just driving.

Like a madman in, in that weather. And again, you know, you got a big jump. You’re going back to the V 12, now all [00:45:00] of a sudden you got 320 horsepower in these cars, in these v twelves. And again, you know, in the two 90 mm, you know, it’s an open top by himself. A magazine asked how fast the car was, uh, he said how he spent time to 179 miles an hour.

No. So your top speeds increasing. Yeah. Know you’re thinking well, oh, okay. That’s not so fast. But I mean, you. Think about what they’re driving on the roads. They’re on just everything. They’re tapping those things out as fast. They could go on a lot of those sections that they could. That is, I think if you’ve only ever, you know, done 120 miles an hour on the highway late at night with the windows up.

Sitting in your leather chair with your Bose stereo and your Mercedes Benz or your BMW, or, you know, in a modern car, you just have no idea of what 120 mile an hour was like in an open car, like that car that Castellotti, uh, won in. You doubly have no idea what, I mean, for me on sports bikes, right, at 120, you can move the bike, at 150, getting the bike to [00:46:00] change direction is really hard.

When I watch motor GP guys flip the bikes over at 170 or 180 miles an hour, I have no idea how they do it. It’s not just the dexterity of the lines. It’s the whole physical thing. Well, well, Castellotti in that Ferrari, 180 miles an hour. I mean, he lost his visor. And the race reports would talk about how he was in a lot of pain because the rain was cutting out his face.

And you’ll even see some pictures where he’s raising his hand. He’s driving one hand and he’s got his hand across his face because the rain is coming down and cutting his face so much. He’s, and he’s, he’s got goggles and used goggles for the, after the visor blew away. Yeah, just impressive. Do you want to say the manliness?

I don’t know what you’d say but just just the dedication and commitment these guys had, you know, a lot of guys you would think that they would just stop after that, you know, be like, I can’t see or I can’t do this or it’s just, you know, unstop them. It’s gladiatorial and it’s about honor. You know, Castellotti was a wealthy landowner [00:47:00] from, I mean, we’re in California now, there’s a town just near here, Lodi.

He was from Lodi in Italy, which is, you know, Northern Italian town. And he wanted to put Lodi on the map. He was a handsome, wealthy guy. He could have just been a playboy. Instead, he really wanted to prove himself. He did date a movie star, Delia Scalia was her name. She had one of these page boy haircuts, a bit like Steve McQueen’s wife.

The Italian press used to love it because, you know, he would, at the Rome Control, they shared a kiss and obviously that was the great fodder for the front pages as opposed to the back pages of the news. And again, it came down to personal preference had to do with the weather, you know, and just all the, you know, circumstances these guys were driving in.

But you had Quite a few more coupes, closed top Ferraris running in that event as well. You know, you had your 250 GTs in that and running in them. And as we know from previous ones, a lot of it was personal preference of the driver. Now, Enzo’s philosophy was, no, you only can win in an open top car. I think a lot of these guys like, [00:48:00] well, I don’t think you could see what the weather or maybe figure it out.

But a lot of these guys chose to run closed top cars. And that race as well, too. Villaresi argued with Ferrari and then in 51, Villaresi won in a closed car. Yep. The quote was that he didn’t want to drive in a bordello of noise, which I, I feel like the, whatever the Italian for a whorehouse of noise is, it’s probably more dramatic sounding than that.

That’s what it is, right? The. You know, I drove half of the route in a Fiat Punto rental and I drove half of the route on this RSV Mille and the RSV Mille, it had a performance and the experience was similar to, I think the way it would have been in the faster cars, of course, the Punto was directly similar to the vast majority of the cars doing the route.

And I, and I do think the interesting thing for me about that was I drove down the Adriatic coast to Pescara. And then when I turned inland at Pescara, I couldn’t believe how quickly the roads changed. I literally. Nearly slid this Punto off because you’d been used to these straights where you could [00:49:00] just like run flat.

And I actually did the Autostrada down the coast now because the old coast road, it’s all tourists and so on now. So you can’t run at the representative speeds. Whereas I felt on the Autostrada, I could like run at a representative speed. But once you get off those straight roads, it’s immediately super mountainous and twisty.

And I nearly put this Punto, uh, off the road. What you saw, I’ll say the introduction, but the, uh, show up is the 500 TR as everyone usually calls the Testarossa showed up, but now it was only a four cylinder wasn’t a 12 cylinder, but yeah, they had one 500 TR entered in that race. He retired now all of a sudden you have that name that kind of is very synonymous with Ferrari.

Testarossa, the redhead, all of a sudden show up in that race. Just not for nothing, right? Genius marketing. Dasher Redpaint. And you’ve a whole model name. You’ve created a whole. I’m put in mind of Picasso in his later years, who would like, if he needed some money to pay for a restaurant bill, he would draw a sketch and then sell it [00:50:00] to another one of the patrons in the restaurant.

And that would pay for his meal. But he literally, like, on the napkin, he’d just, like, draw whatever he felt. And if you look at his later art, it really has that feeling of, I’m going to draw whatever I want to create. I want to just hit a slightly macabre note here. Six deaths in 1956. A series of different accidents.

I’ve not drilled into who, why, what went out. But this really speaks to the fact that this. Is a city to city road race, which was always dangerous. But when we were doing city to city road racing and the cars were doing 120 or 140, that was really dangerous, but that was. You know, maybe not lots of people would be killed.

Now we’ve moved to the stage where the cars are doing 180 miles an hour. That little bump, now the car’s fully airborne over that little bump. Now I know when we talked about it with Sterling Moss a [00:51:00] minute ago, it was a wonderful story and it was like the Dukes of Hazzard and what plucky Brits. But really, if you stop and think about that, looking back, It’s impossible to imagine that the people organizing the Mille Miglia didn’t believe that it was just a matter of time before there was a horrific accident.

You feel like everybody was relying on, you know, the Virgin or fate or somebody to save us. Cause literally you can’t race 180 mile an hour cars through crowded streets without sooner or later that the being, you know, the big one as they call it. And of course that was. 1957. I don’t mean to just kind of gloss over it, but every year, I mean, it wasn’t like one or two, you know, there was a decent amount of people getting killed in that race every year.

And, you know, I don’t know if it had to do with the fact is obviously in the time, you know, you don’t have, you know, the AP wire and all that kind of stuff. You don’t have the internet, obviously, or anything like that, but there were significant amounts of people getting killed in that race. You know, year in, year out and not, you know, drivers.

Yeah, but there were spectators as well that were [00:52:00] getting killed at these races. 57 obviously was, you know, the capper of it. It’s all Jesus, you know, kids and everything like that. But if you look going back to that race, there was every year, there was a, you know, 5, guys dying racing. But then there was also a spectator here or there or whatnot.

Also, you know, got killed as well, you know, wandering out in the road or whatnot. Because as much as they tried one, hey, they, all the roads were closed. Now you’re going to have a few of those. Old Italian guys and their farmers and whatnot saying, I don’t give two shits. This is, you know, I’m going to keep working and do what I got to do.

And just, you know, wander out in the road and do whatever I got to do, driving a tractor on it. I, you know, I don’t know if people realize that it wasn’t just a 57 that all crap, nine people got killed and kids and everything like that. That, oh, we got to stop it. No, there was death. You’re in, you’re out.

And the other Italians, Braco, rolled a car into a crowd and killed 12 in an event in the 40s. We were slating Braco here, I mean for what it’s worth, Farina also had those kinds of incidents. The way that you need to frame this is you need to see this through the [00:53:00] eyes of contemporary Italians. Mussolini came to power and Italy became a fascist nation.

in 1921. So throughout the 20s and the 30s you have this ethos of survival of the fittest and Mussolini and the Italian fascists believed that the natural state for a nation was to be at war and that there would be some attrition and combat. There would be some death. That was why it was just accepted as part of the sport.

And I think post war, we see that becoming unacceptable. And we see the Pope stepping in and saying, you know what? This kind of carnage in the name of what the greater good, the advancement of Italian motorsport. And that’s what Taruffi says that early on, it felt like you were really advancing the art of automobility.

Whereas by the fifties. It’s not really like that. We’ve sort of outgrown the environment we’re playing. We’ve perfected the automobile. And to be fair, the Mille Miglia is not a special corner case in this instance. Death was [00:54:00] common in motorsport across the board. Whether it was Formula One, Grand Prix racing, Le Mans, Indianapolis 500.

It’s just a sign of those times. And as a result of that, safety equipment got better. It didn’t get better for a long time because even folks like Sir Jackie Stewart were still fighting for safety in the seventies. We have really taken leaps and bounds in that department in the modern times. But what’s important about this particular story and how it comes to a head with the Ferrari movie that just came out is 1957 is sort of the wreck that changed the world, especially the motor sports world.

And John, you foreshadowed this about the Italian drivers. And Taroufi was one of the last of the old guard in this sense. And he’s quoted as saying, stop us before we kill again. We need to get our arms around these races and the Mille Miglia, especially because it’s a bit more wild west than organized races that were sanctioned by the FIA.

Like Le Mans and some of the other ones that were out [00:55:00] there. So the movie depicts this horrific crash of Portago. And I’ll let you guys kind of explain that and why it’s significant and how it changed motorsport from 1957 forward. Ferrari for the mille mille has four cars, two, three, three fives. Two, three 15s that the difference is, you know, some are a 3.

8 liter. The others are, are a 4. 1. So, you know, you fast and effing fast. Basically you have a driver lineup, which is focused on young up and comers. And you’ve also got Ferrari who is recently grieving from the loss of his son. And I don’t know if the movie speaks to this or not. I’m yet to see the movie.

I’m really looking forward to seeing it. You know, I deliberately wanted to do this call and talk about. The 1957 Mille Miglia and talk about the Mille Miglia and Ferrari in general, before I’ve seen, you know, Michael Mann’s interpretation of it. I’m fascinated to see Michael Mann’s interpretation. In those Ferraris, you have young up and coming Formula One drivers, Peter Collins, Wolfgang von Trips, [00:56:00] Alfonso de Portago, and the old Italian charger.

Tarufi, by the way, we should just do a thumbnail on the Pataco for a minute, Spanish, half a dozen different titles, a wealthy playboy, Spanish champion, I think tennis, maybe golf as well. Bobsleigh champion, you know, set a record time on the Cresta run for people who understand bobsleighing. I can’t pretend that I do, but I even, I understand what the Cresta run is.

Maybe it was because of those Vauxhall Crestas. 1960s that my grandfather had. But no, DePortago is this all round sportsman who established himself as a racing driver. People thought he was just a wealthy playboy. There were plenty of them that tried to participate in Formula 1, but no, DePortago was the real deal.

Earned his place on Ferrari team. Although I would say that one of my favorite stories about him is that the way that he recognized his car was when they were first allocated the car, he would scratch a mark on the dashboard by the rev counter. So he recognized his car. [00:57:00] And I just think of that every, and the next time you’re at a Ferrari event and you’re looking at all of these dudes picking the gravel out of the tire, just think about Fond de Portago.

And just, I just put a scrape in it with a screwdriver there. So I know which car’s mine and yes. All the others of the Italians are gone by this time. And Taruffi is left with this burning desire to win the Mille Miglia. At the time, Ferrari has this rather odd relationship with Peter Collins. I think reading between the lines, he sort of adopted Peter Collins sort of as his son.

And then when Peter Collins got married, he sort of, you know, stepped away from that. But there was some very bizarre thing going on. And in the stuff that you read about Castellotti, The Italians were upset that Ferrari favored the blonde haired British boy rather than, you know, the Italian in terms of the cars that they gave them in Formula One at least.

The Ferraris that enter in 1957, I would say if we roll with this five miles an hour faster each [00:58:00] year, what we’re saying is these are 185 mile an hour cars, which is stupefying, frankly. Still on six inch tires. Yeah. 360 horsepower under 2000 pounds. And this pattern and William, you touched on this in the last episode that with Ferraris, the ancillary components fail, it’s the suspension.

It’s the steering. It’s the gearbox. It’s the back axle. It’s not the engine. The rest of the car will fall apart around the engine. And certainly with these big capacity, 12 cylinders with the amount of torque they produce, they are gonna just. Take apart the drive train. Hey, Dean Batchelor, the editor of car and driver.

He was super keen hot rod guy, but a super keen Ferrari guy. And he wrote about these big capacity V12 sports racing Ferraris because the gas tanks were over the rear wheels. When you got in the car in Brescia at the start, the car’s got fresh suspension, [00:59:00] fresh brakes, and a full tank of gas. By the time you’re at Rome, the tanks are empty, so it’s handling a completely different way.

You gas up at Rome, and now it’s handling a completely different way again, because now it’s got all that weight at the back, but the suspension and the brakes aren’t what they were before. The line that Batchelor has is, they were not for the faint hearted. You really need to be on the case just to survive the race, let alone win.

Yeah. You’re talking like 35 to 40 gallons of gas. You’re not talking 10, 20. I think Moss is SLR had a 50 gallon tank. Yeah. That’s a lot of weight. Yeah. A lot of weight. And to your point, you know, when everything kind of breaking down and all of a sudden you get to a point where all of a sudden this car is driving completely different because you got hardly any gas and then all of a sudden it’s just taking a beating and then all of a sudden you dump.

Three, 400 pounds of gas back into this thing. Cause that’s probably what you’re probably talking about easily. Yeah. All of a sudden it’s just going, it’s like behind your toes. I wonder, you know, Ferrari had a falling out with his tire maker [01:00:00] in 55 and Marzotto retired or one of the Ferrari guys retired when a car threw a tread and the spare that he had didn’t fit.

And it was cause Ferrari had these like issues with tires and you do, you wonder. Let’s tell the story of the race a little bit that the Ferraris are dominant and trade the lead amongst each other. Peter Collins is leading but loses a transmission. So the race is between Tarufi and Von Trips right in the finishing stages.

DePortago loses a tire, we think, probably lost a tire, and without wanting to go into detail, there is horrific detail out there now, and I’m not seeing the movie, maybe the movie will even do it, my understanding was it was one side of the road in a ditch, the other side of the road in a ditch, through a wall, there were some people on the wall, a lot of children, both Edmund Nelson, DePortago’s co driver, and DePortago himself, gone [01:01:00] immediately, and with it, Really the end of the Mille Miglia because the Pope gets involved, there’s talk of excommunication, Ferrari faces manslaughter, charges, an interesting story which an Italian told me and may or may not be true, but when you drive in Italy now, there are not cat’s eyes in the middle of the road.

You know, the reflectors in the middle of the road in Italy, they don’t do them. And apparently I’m not research this, but what he told me was the, the reason that they don’t have cat size in Italy was that it was decided that the reason the Protago’s tire came apart. was because he skidded over a cat’s eye and that’s what caused it to come off the rim and crash.

So cat’s eyes were the cause of the accident, not that you’d raced for 900 miles, uh, more than 170 miles an hour on dodgy cross ply, narrow tires. And there was none of that in a 400 horsepower car. No, no, it was none of that. It was those cat’s eyes caused the accident. [01:02:00] So all of this overshadows To Rufy’s really pretty, awesome, considered balanced drive.

And, and really every other Mille Miglia, he’d always been there, but there’d always been some, if you know Indianapolis 500 history, there’d always been some kind of Lloyd Ruby moment where, you know, the car had gone wrong or one year a backmarker moved into his path and forced him off the road when he was leading, you know, he had, his hat was in the ring every time since 1930s.

And now finally, I think it’s sad because You know, they were cheering him. And then after what had happened with the Potago, the cheering was considerably less and it took the edge off what was undoubtedly a huge achievement. I guess the final thing to say is Ferrari, the way Ferrari has it. is that he says to Von Trips at the last control, it would be really nice if Tarufi could win.

And Von Trips, who was a German nobleman who, like [01:03:00] Di Portago, was racing for honor, racing to prove himself, racing to, I think, to establish. himself as something different from what everybody knew Germany had been just a few short years before. In Von Trips you really get the sense of a gentleman driver wanting to prove himself.

So Von Trips, according to one version of the story, allows To roofie to, to win to roofie’s version is to roofie had nursed the car. The car was stronger and on some bends, just outside Cremona. He’s able to demonstrate to Von Tripps that he’s better and able to win the race and goes on and wins again.

More research is probably required into that one, but hats off to to roofie. And that is the end of the melee milieu. But is it really the end? So because of that crash, it puts a huge dark cloud over motorsport and they press pause on the Amelia Amelia. But if you jump us forward a couple of [01:04:00] decades, it’s reborn.

And the rebirth. is absolutely about the time there was a proper collector car movement established that really before the 1970s, there was no real collector car movement into the 1980s. That was the beginning of a collector car movement. And those of us with gray hair will remember that there was a bit of a boom.

Well, there was more than a bit of a boom. There was a huge boom in Ferrari prices in, in the late eighties. And, and around about that time, the Mille Miglia was reestablished as a historic motoring event. You know, we arrive in Brescia, the look and feel in Brescia is very similar to the way that it was cars that are invited to.

Participate of the cars that participated years ago and the Italian government is involved in, if not in closing the roads in providing a police escort to allow the cars to drive the route of the Mille Miglia, but now we stop in nice [01:05:00] five star hotels, eat nice food and patch each other on the back and remember days of your, and if that sounds.

A shadow of the event as it was. Yes, absolutely. It is. But if you talk to anybody who’s participated in modern millimilia, they’ll tell you that it’s really hard to enjoy that five star food because, you know, you’re up at six in the morning and you’re responsible for looking after the car and you know, those Italian police convoys, they will let you run.

Autobahn speed, you know, more than a hundred miles an hour. They love motorcycles, BMW motorcycles. So, you know, the Italians have a passion for motorsport, which carries through to this day. So it’s a, it’s an awesome event. Is it what Moss won in 1955? No, because that was nonstop. This is. Very much the feel of it.

And it would be an awesome event to do if I was wealthy enough to do it. I know one guy I in, uh, actually used lives in Lodi who did the event a [01:06:00] few years ago with a guy who has an alpha Romeo and he did it with this guy. Because years ago, my friend, Phil, his skill. Well, he has many skills, but his skill is Corvette mechanical fuel injection.

And he was at Goodwood one year and the guy with the Corvette with the mechanical fuel injection, he could tell the car wasn’t running properly. So he helped the guy tune his Rochester mechanical fuel injection. And the guy was like, you are welcome to my house whenever you wish. And it turns out the bloke was an English Lord.

With the hot rod guy from Lodi, who just happened to really know how to do the Rochester mechanical fuel injection, was able to help the English Lord win the Goodwood race in the Corvair, and thus was invited to do the Mille Miglia in the Alfa Romeo a few years later. So, Yeah, a significant digression there, Eric.

I’m sorry about that. No, but you bring up a very valid point in the sense that the Mila Melia in some ways can be compared to Goodwood and on a grand scale, [01:07:00] countrywide in Italy, it’s Italy’s version of Goodwood now. And that’s something to. Appreciate but also celebrate and it’s nice that we can be part of that again and it’s not something that’s just lost on the pages of history that pun intended died in 1957.

It’s now still alive and vibrant and in a new way, but in a good way. Trying to, I guess they corral everyone and keep everyone in check, but not everyone follows it because they want to be doing the, they got these great cars, so they want to open them up, but there’s all the times like it’s a rally. So they have all these different sections time wise and whatnot.

So in a way it’s trying to hold people back because if you’re familiar with how those work, you know, Hey, you got A to B got, this is what you’re supposed to get to B. And so they try and crowd people in, but. You see it all the time and you see videos like that, you know, you got guys crash and whatnot because they’re just going balls out in their car because if they want to do it, you know, the town police, they’re more than happy to, uh, help you out in that manner and get ahead of you and clear traffic.

It’s an interesting event and don’t necessarily have to own a car. There’s actually a few [01:08:00] companies that have cars that you can go and they actually do the whole thing. You rent the car or everything like that and do it. So. You know, you don’t have to necessarily have to have a car pre 1957 to have to compete in it.

You know, there’s several different ways to participate. It’s an interesting event, but again, as John said, it ain’t cheap. Because they drive past you as well. I mean, you can also go and, you know, have your Italian vacation and, you know, be there as the cars drive by, you know, it’s free to go and be in Brescia.

At the start, you know, I’ve not been, but the atmosphere of that, when you see film of it, it looks and feels exactly the same as it did in period. The kind of people who participate, it always was wealthy, showy people. I mean, think of the Marzottos and they’re, you know, wearing their shirts and ties. I mean, that it’s always been that kind of event.

Yeah. It’s always been part motor sport, part Italian festival. You have a lot of people too, that just. Have a modern car and just follow along and drive in it because it’s not like the route’s a secret, but I mean, you could have a rental [01:09:00] car if you want to go over there and just follow the route and follow the people and stay in your own place and everything.

Then kind of pseudo take part in it. But Hey, if you want to check it out and see it, I mean, you’d be amongst all the cars and the competitors and hanging out and doing what you have to do. And from my understanding, no one really cares. Hey, you’re having fun with it as well. You’re just not staying in the five star hotels and.

Kind of, as John says, how much you’re actually enjoying that because there’s some days you’re driving for 12, 14 hours. Yeah, and if you’re doing that in an open car, you are beating it up. Guys, I have to say this two part history and celebration of the Mille Miglia has been an education. The collector car information, the history of Ferraris coming from William and John, you bringing this plethora of information about the stories and the drivers and the adventures that were happening during the millennial.

I come away from this in awe. There’s a lot of things that I knew or I had heard in passing, but I feel like I’m more familiar with the stories now. I feel like I’m closer to the race and I appreciate you guys spending the time [01:10:00] to educate not only me, but the audience that’s listening to these episodes as well.

Yeah, I got, you know, um. Obviously we could have got a lot more in depth. I mean, not saying that we didn’t get in depth. I was gonna say the first part of this thing was like, what, you know, hour and a half over, it was two hours long, just so much more information in detail. Cause as you go into the years, you can see, you know, you had three, four cars with Ferraris around, but then by the end there’s 20 plus cars in the event, you know, Ferraris.

So, you know, it’s, it’s a great, great event to really kind of dig into. So I highly recommend, you know, there’s plenty of books out there. There’s a great reference book that I use is it’s probably one of the guys could be Giano Marzotto wrote it called Red Arrows Farmer’s at the Mill. Amelia. It’s a great book.

It has everything about all the fires are participated. It goes throughout all the years. I think that’s fantastic. Book gives you chassis numbers, everything like that. So if you really want to get into something, it’s not a cheap book because they didn’t make many of them. But, uh, it’s a great book to hunt down, you know, appreciate everyone listening.

And like I said, I think we only scratched the surface of what we get into, but. I think we kind of gave everyone a good listen and a good overview of the middle of million and definitely recommend [01:11:00] doing a little more digging into it. And, uh, so I want to thank Eric for, uh, being our moderator and pundit in this and helping us out.

And obviously John, the motor and historian, you know, helping out as well, giving us all the history and background stuff, cause you definitely have these, these guys will be back on definitely some other ones down the road, we’re looking at, you know, Targa Floria as well, and some other events. So, uh. Keep your ears peeled and eyes open for those when they drop.

So, but again, I appreciate everyone listening to the Ferrari Marketplace. Get yourself hooked up on the MPN, the Motoring Podcast Network, because we have a lot more episodes, a lot more podcasts that will be getting dropped onto the site and we appreciate it guys and enjoy your day. And thank you guys.

Enjoy more Motoring Historian Podcast Episodes!

The Motoring Historian is produced and sponsored by The Motoring Podcast Network

Copyright William Ross, Exotic Car Marketplace a division of Sixty5 Motorsports. This episode is part of Gran Touring Motorsports, Motoring Podcast Network and has been republished with permission.